British Museum Celebrates Gay History

The British Museum has launched a book about same-sex relationships through history to raise awareness about an "overlooked aspects of the human condition".

Richard Parkinson has launched A Little Gay History and will discuss the book at the museum on the anniversary of the 1969 New York Stonewall riots, a key moment in the fight for gay rights.

The book asks questions such as: Who was the first lesbian? Were ancient Greek men who had sex with one another gay? And what was the oldest chat-up line between men?

It examines objects from ancient Egypt, images of erotic scenes on the Roman Warren Cup, and work by modern artists such as David Hockney and Bhupen Khakhar.

A Little Gay History follows the British Museum's web trail, "Same-sex desire and gender identity", which was launched as part of LGBT History Month in 2010.

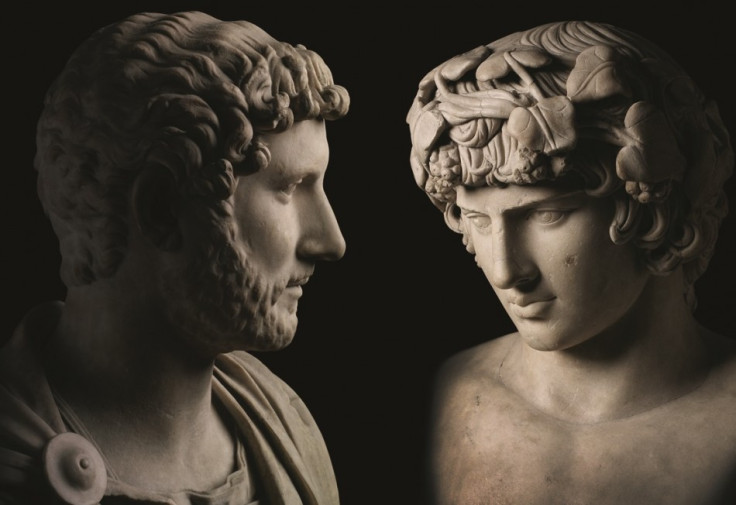

The trail has been expanded and updated to coincide with the launch of the book. Among the added artefacts is a sculpture of the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar, who had the power to change men into women, and the statues of Hadrian and Antinous. Hadrian mourned the death of his lover Antinous by commemorating him in many effigies.

It also includes an 1818 letter to William Bankes, a gentleman who was forced to flee England after being caught having sex with a soldier.

In the book, Parkinson says: "We want to show the depth of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender history and its presence in every continent across the world. Homosexuality is not just the well-known 'Greek love' of ancient Athens."

He continues: "An engraving by the Italian artist Marcantonio Raimondi from the early 16<sup>th century shows the Greek god Apollo with his beloved Hyacynthus. This was produced in an age when men could be killed for acting on [these] desires.

"In looking for love in history, we need to remember that art is never simply a reflection of social reality. Much ancient Greek art, both domestic and public, displayed naked male beauty as an image of physical, social and intellectual perfection, even though public male nudity was not common except in athletics grounds.

"In this case, however, we can be fairly sure that such art had an erotic aspect for the intended (male) viewers."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.