Darpa develops brain chip that collects electrical signals and sends them to a computer

Australian scientists funded by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) have developed a transmitter device that can be injected into the brain without invasive surgery and then used to collect electrical signals and then send the data to a computer for analysis, which is a breakthrough in making brain machine interfaces possible.

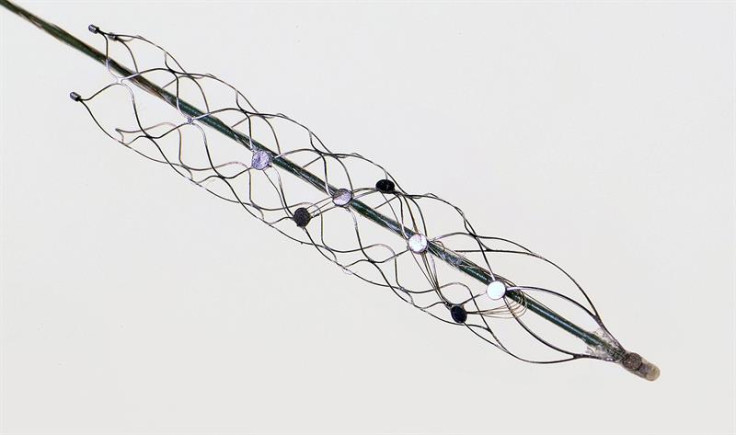

Researchers from the University of Melbourne have invented the stentrode – a device the size of a paper clip that is basically a tiny stent that comes with an array of electrodes. At the moment, the only way to put electrodes into the brain is to open up the skull during surgery. Instead, the stentrode is flexible enough to be able to pass through the brain via curving blood vessels, yet stiff enough to work properly once it arrives at its destination.

It is inserted into the brain via a blood vessel in the neck and then guided by researchers armed with real-time imaging to a precise location in the brain, where it expands and attaches itself to the walls of the blood vessel in order to read the activity of nearby neurons.

The team, headed by neurologist Thomas Oxley MD of the Vascular Bionics Laboratory, have been working on the neural recording device for the last four years and they were successfully able to implant the stentrode into a freely moving sheep, and then record brain signal readings for up to 190 days after it was implanted.

Their research, entitled "Minimally invasive endovascular stent-electrode array for high-fidelity, chronic recordings of cortical neural activity" is published in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

Next stop, implanting chips in humans

Besides showing that the device would be safe for long-term use, the study also showed that the signal measurements were similar to those taken by surface electrocorticography arrays that are implanted during open brain surgery. The next step would be to trial the brain transmitters in humans in 2017 at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia.

"DARPA has previously demonstrated direct brain control of a prosthetic limb by paralysed patients fitted with penetrating electrode arrays implanted in the motor cortex during traditional open-brain surgery," said Doug Weber, the program manager for Darpa's Reliable Neural-Interface Technology (RE-NET) programme, which is trying to expand and develop the use of brain-machine interfaces to treat physical disabilities and neurological disorders.

"By reducing the need for invasive surgery, the stentrode may pave the way for more practical implementations of those kinds of life-changing applications of brain-machine interfaces."

Interestingly, back in September 2015, IBTimes UK wrote about a book by journalist Annie Jacobsen claiming that Darpa was already embedding such computer chips into the brains of injured soldiers coming back from the Middle East with the intent to help treat the disorders, and a PowerPoint slide describing the how the system would work was leaked onto the internet.

When we published the story, we were contacted by Darpa, who insisted that they were not implanting chips into the brains of humans, yet they did not call Jacobsen's book a lie. But with this new research endorsed by Darpa, it seems clear that there is definitely something going on, and Darpa definitely wants to connect the human brain to a computer.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.