Ebola Panic Hamstrings South African Tourism While Bigger Insidious Disease Goes Unnoticed

Although South Africa has had no confirmed cases of Ebola and is thousands of miles from the epicentre of the epidemic in West Africa, it appears that its tourist industry is being hammered anyway.

According to local reports, panic over the disease is reminiscent of that generated by SARS in 2003, causing holiday-makers from Europe, the US, and particularly Asia, to cancel their travel plans to the country in droves.

Enver Duminy, chief executive of Cape Town Tourism, told national Sunday newspaper City Press over the weekend that even though the organisation had issued numerous statements confirming the Mother City's ebola-free status, its Asian tour promoters and trade contacts were experiencing cancellation rates of up to 90%.

This is despite the fact that Cape Town is further from the centre of the epidemic in Freetown, Liberia (3,365 miles) than it is from London (3,172 miles).

As unwarranted as such fears may be, they could potentially be disastrous for the local economy. Tourism is worth about ZAR18bn (£1bn) to the Western Cape, South Africa's largest sightseeing destination by far, and the industry employs 150,000 people.

Across South Africa as a whole, tourism contributes a significant 9% of GDP and accounts for one in 11 jobs, making it a hugely important and often underestimated industry.

In a bid to help try and prevent the spread of Ebola to South African shores, Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene has allocated an extra ZAR33m (£1.9m) to help support the continent's worst affected nations – Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

Each of South Africa's nine provinces has also designated certain key hospitals to handle an outbreak should one occur, introduced trained response teams, and implemented surveillance at all ports of entry, including thermal scanners at Johannesburg's OR Tambo and Lanseria airports.

Such preventative measures would appear to be vital. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), as of last week the disease has killed 5,160 out of the 14,098 people infected in eight countries across West Africa.

Insidious Bilharzia disease gets little international attention

Another dangerous disease worth considering, even though it has received nothing like the global attention of Ebola, is bilharzia – or to use its scientific name, schistosomiasis.

Despite being a rather neglected condition to date, the WHO expressed concern last month that the spread of bilharzia may be about to hit epidemic proportions in South Africa.

It is estimated that as many as five million out of a total population of 53 million could be infected, with the problem being particularly acute in Kwa-Zulu Natal's (KZN) humid, low altitude coastal areas.

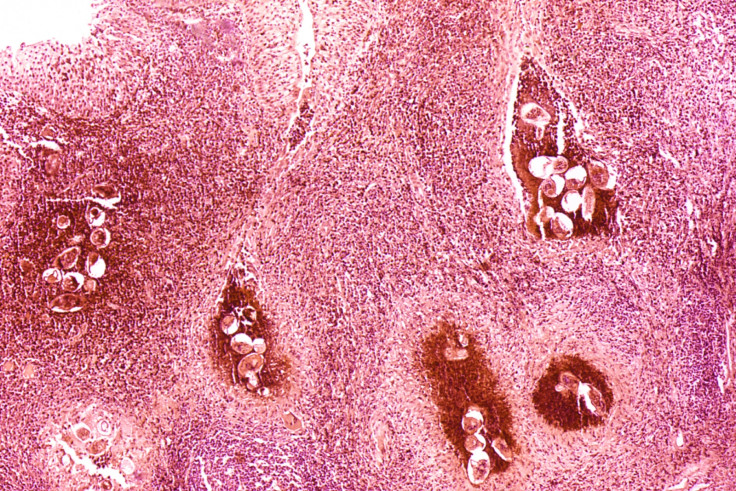

The disease is caused by a schistosoma parasitic flatworm that enters the skin through contact with infected fresh water in rivers and lakes. These parasites, which can live in the blood stream of their host for up to 30 years, develop over time into worms, which mate and release up to 500 eggs a day.

Some of these eggs are passed out through urine or faeces, while others remain trapped in body tissue, the most common areas being the intestine, liver, bladder, and reproductive organs, causing inflammation or scarring in the process.

While symptoms vary, for many people they start with a rash or itchy skin within a few days of infection. The next stage is often a fever, chills, a cough, muscle aches, and diarrhoea a couple of months later.

But, while the illness takes a number of forms and can even remain dormant in people's systems for years, the ultimate outcome is generally immune problems and progressive organ damage.

While children are most vulnerable to the disease, it is actually its effect on women that is causing most concern to experts. Estimates are that about two million South African females are currently infected with bilharzia, which can cause severe gynaecological issues, including infertility.

Other problems include severe pain and chronic bleeding, particularly during sexual intercourse, which means that women are as much as three times more likely to contract HIV/AIDS - a disease already at pandemic levels among disadvantaged women in rural communities - if having sex with an infected partner.

Even more worryingly, the WHO believes that more than 150 million women across the continent suffer from this generally unrecognised form of the disease.

Taking action

There are things that can be done. If diagnosed early enough, the worms can be killed off quite easily with a single doze of the drug praziquantel, although the eggs cannot.

Children in particularly affected areas of South Africa are already given such medication once every two years for prevention purposes, although some experts believe that an annual dose would probably be more appropriate.

But there is currently no vaccine for bilharzia and, to make matters worse, the illness tends to go largely unnoticed or misdiagnosed. Too few medical practitioners are even aware of its existence, and those that are tend to look for blood in the urine as a primary symptom, which is not necessarily the case.

As Dr Eyrun Kjetland, an honorary lecturer at KZN University and the Norwegian Centre for Imported and Tropical Diseases, told a gathering of WHO experts, African doctors and leading researchers at the University last month: "It is a neglected tropical disease and there's not a lot of attention on it. The pharmaceutical companies don't care about it, there's no donations coming forth and the authorities are not doing enough in paving the way to make it less of a public health problem."

As a result, she is currently working with a number of other health experts in order to compile an information booklet. The document, which is due to be published within a couple of years, is intended to help doctors recognise the condition and treat it more effectively.

A team from KZN University is also undertaking research on the province's south coast, where infection is rife, in a bid to come up with a wider plan of action for treatment and prevention. To this end, a draft report is already in the pipeline – and so it would appear, not a moment too soon.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.