Kurdistan: The Most Dangerous Word in Turkey [BLOG]

Kurds engaged in endless battle to preserve cultural identity and keep their flag flying in Turkey

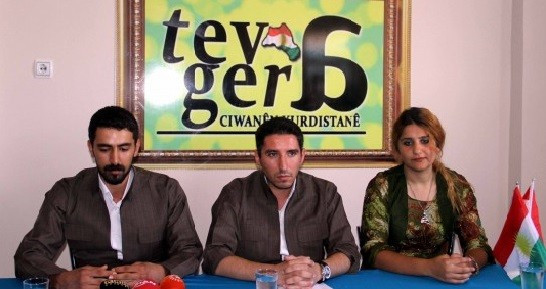

On 6 August, 2013, the name Kurdistan was hung out on a sign in the Kurdish province of Diyarbakır for the first time in Turkey's history when a group of Kurdish activists decided to establish a Kurdish cultural association. It was called Komeleya Tevgera Ciwanên Kurdistan (Kurdistan Youth Movement Association).

Given that the use of words "Kurd" and "Kurdistan" was forbidden in Turkey for years, establishing a legal association with "Kurdistan" in its title is an enormously progressive act .

But investigators have ruled that using the word "Kurdistan" is against the Turkish constitution and penal code. The founders of the association have been threatened with life imprisonment. once again, state intolerance is on display.

The Ministry of the Interior ruled: "A person who commits an act to put the whole or a part of the territory of the state under the domination of a foreign state, to disrupt the unity of the state, to separate a part of the state's land from the rule of the state and to cripple the independence of the state shall be given an aggravated life imprisonment."

"If Kurds are told to lay down their arms and engage in politics, obstacles before Kurds to participate in legal politics should be eliminated," Serhat Mérdînî, head of the association, replied.

He said that the Kurdistan Youth Movement Association held no ties with any organisation or political party. It consisted of young people with an independent way of thinking.

"There are walls of fear in Turkey. We would like to tear down those walls," Mérdînî added.

"We are a distinctive association that defends [the right of] individuals to their free will, their own thoughts. We would like to break the taboos imposed on Kurds by the power elite.

"There is a German Cultural Association near our association. I am from the Kurdish province of Mardin. And in Mardin, there is an American Cultural Association where the American flag is waved. People come from thousands of miles away and establish associations here. So what is wrong with our using the word 'Kurdistan' as the people of Kurdistan," Mérdînî asked.

He continued: "When Kurdish rights are discussed, even seemingly the most democratic individuals have this phobia stemming from a colonialist mentality. This mentality must change. If a sustainable peace is to be achieved in this country, a new mentality that sees Kurds as equal citizens should be adopted. It should be recognized that Kurds are a distinct nation.

"They will probably file a suit against us in a month. We will attend the trials and take legal action. In the event that domestic remedies are exhausted, we will take the case to the European Court of Human Rights."

He said that if the association were allowed to function, it would focus on cultural and linguistic activities for Kurdish youth, including Kurdish language classes and symposiums, conferences and seminars on Kurdish history.

"We would particularly carry out activities to enhance the physical and intellectual development of young people."

Recognising the right of Kurds to self-determination is the sole remedy for achieving peace, Mérdînî said.

"If opinions are to be discussed, we believe that silencing the guns is the right thing to do. But I don't think the guns will be silenced as long as they don't come up with a just solution to this problem. Establishing a federation could be the solution."

In 1925, the country of the Kurds, known since the 12th century as "Kurdistan", was forcibly divided between Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria. And for the first time in its long history, it was deprived of its cultural autonomy.

Ever since that date, Kurds in Turkey have been denied their basic rights and freedoms as the state attempts to assimilate them.

For 90 years, successive governments have viewed the expression of a Kurdish identity as a potential threat, denying the historical fact that the Near East is an eminently multicultural, multiracial and multinational region.

Uzay Bulut is a freelance journalist based in Ankara

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.