MIT develops creative drone that can mimic drawings

A new project from MIT Media Lab's Fluid Interfaces Group is exploring the creative potential of drones by putting a modern twist on the pantograph to create a flying drawing machine. Dubbed the "Flying Pantograph", the drone can follow pen strokes of a user and mimic the sketch on its own canvas.

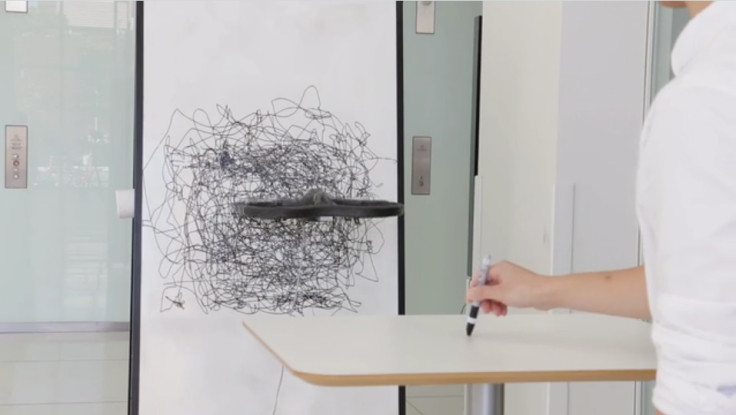

As a human artist makes drawing movements with a pen, a camera captures the motion. A computer then communicates to the drone that mirrors the flow of the pen to create a similar mark on its own vertical canvas. Created by students Sang-won Leigh, Harshit Agrawal and Pattie Maes, the drone takes its name from the original pantograph, first created in 1603, that links two writing devices together to duplicate or scale a drawing on a different piece of paper.

"Since pre-historic time, humankind has been involved in drawing through a myriad forms of mediums that, over many years, have evolved to be increasingly computation-driven," the team behind the technology explained. "However, they largely continue to remain constrained to human body scale and aesthetics, while computer technology now allows a more synergistic and collaborative expression between human and machine. In our installation, we engage audience with a drone-based drawing system that applies a person's pen drawing at different scales in different styles. The unrestricted and programmable motion of the proxy can institute various artistic distortions in real-time, creating a new dynamic medium of creation expression."

A Flying Pantograph from Fluid Interfaces on Vimeo.

However, the drone's drawings, while impressive, are not as accurate as one would hope. According to Sang-won, the first version of the drone, which used a motion-tracking system to watch what the pen was doing and then send commands to a laptop over Wi-Fi, was less controlled.

"Now we have better control capacity so that we can fairly easily draw straight lines," Leigh told Wired, but added that "there is huge room for engineering, to be fair".

The drone still has to maintain balance as it battles air currents, friction from the canvas and the raw movements from the artistic to create the drawing, resulting in often shaky versions of the intended sketch. It also seems to read slow, careful movements much more accurately than quicker, longer gestures which tend to interrupt the drone's actions and alters the image.

However, the team says the drone's unpredictable, shaky nature allows the machine to add its own creative flair to the drawing, making the end result more of a collaboration than mere mimicry.

"From an art perspective, we found this very fascinating," Leigh said. "In this we found room for machine creativity seeping into the artistic act of a human."

With drones being used for more creative purposes of late, from filming lavish weddings and being attached to a flame thrower to delivering a pizza, one can certainly imagine the new artistically-inclined technology being put to good use. It could allow multiple artists to collaborate in real time without being in the same country, let alone the same room, or allow them to paint on surfaces that are either too far or too large without stepping off the ground.

The machine could be refined using a more sophisticated drone for more precise drawings. Altering its input methods with EEGs, eye-tracking software and VR control options could also potentially help a person with a disability write messages or create art.

"One of the most innate things a human can do to be creative is draw," Agrawal told Fast Company. "If our creativity is going to escape our biological limitations, finding new ways seems like a natural extension."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.