Pope Francis visit to Africa: Where the Catholic Church grows faster than anywhere else

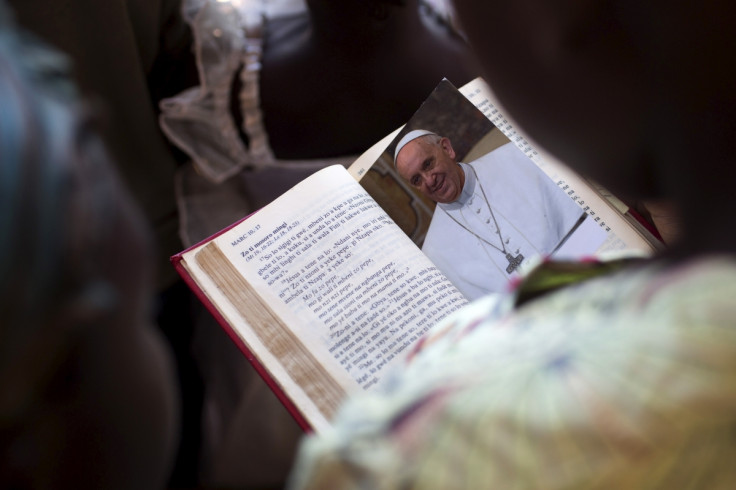

Pope Francis will be making his first visit to Africa over five days, starting off in Uganda on 25 November where he will hold a mass for Christian martyrs at a shrine at Namugongo and meet young people at the Kololo airstrip in the capital, Kampala.

His delegation will then visit Kenya, and the Central African Republic (CAR) – some of the countries where the Catholic Church is growing faster than anywhere else in the world.

IBTimes UK looks at the numbers behind the region, which encompasses some of the biggest problems facing not only the Catholic Church, but also the world.

Early Catholicism in East Africa

In the past century, the Catholic Church grew from 1.9 million to just under 140 million in Sub-Saharian Africa, according to the National Catholic Reporter newspaper.

Kenya's first encounter with Roman Catholicism was in the 15th century when the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama anchored off Mombasa after going around the Cape of Good Hope.

According to the Dictionary of African Christianity, Muslim inhabitants had already established a presence on the east coast, and it was not until after 1515 that Dom Pedro Mascarenhas, the Portuguese viceroy of India, instructed that the gospels should be preached to the inhabitants.

Today, countries such as Burundi (62.1%), Rwanda (43.7%) and Uganda (41.9%) have the highest proportion of Catholics in Africa's Great Lakes region, according to the CIA Factbook and national surveys.

CAR's religious and sectarian war

The Pope's delegation is expected to reach war-torn CAR on 29 November. Violence erupted in the country, that is at 37.3% Catholic, when Michel Djotodia, a Muslim, overtook Christian former president and long-time leader Francois Bozize in a coup in 2013. As a result of the unrest, the rebel Muslim "Seleka" movement and Christian "anti-Balaka" militias engaged in tit-for-tat brutality.

Catholicism in numbers

Catholics in Sub-Saharian Africa by 2000: 140 million

Great Lakes country with largest Catholics: Burundi (62.1%)

Percentage of Catholics in CAR: 37.3%

Number of bishops in CAR: 16

Percentage of Catholics in Uganda: 41.9%

Number of priests in Uganda: 2180

Percentage of Catholics in Kenya: 33%

Number of bishops in Kenya: 38

Sources: National Catholic Reporter, CIA Factbook, Vatican Network,

While the Pope already called for an end to the bloodshed in CAR, there are growing concerns the small nation is sliding into religious conflict.

During his Sunday Angelus prayer and three weeks before his trip, the Pope reiterated his message, expressing his solidarity to the Church and to the entire nation "so harshly exhausted while making every possible effort to overcome divisions and return to the path of peace".

Speaking from Nairobi, Lewis Mudge, researcher with Human Rights Watch (HRW)'s Africa Division, told IBTimes UK that the conflict has broken down on sectarian lines "and individuals are targeted because they are Muslim or non-Muslim". Prior to the violence and chaos that started in March 2013, 122,000 Muslims lived in the capital; only an estimated 15,000 remain.

The Reverend Herve Hubert Koyassambia-Kozondo, however, said during a press conference on 23 November that referring to the conflict as religious fighting is incorrect. The clergyman, who is from the archdiocese of CAR's capital Bangui, instead believes the former French colony is being "conquered" by foreign mercenaries from Chad and Sudan.

Kenya: review Church's ban on contraception, says HRW

In Kenya, meanwhile, where more than 13.8 million are Catholics, the Church's blanket prohibition on contraception and abortion harms hundreds of thousands, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimating that women and girls, are also disproportionately vulnerable to HIV infection. In Kenya, 700,000 women above the age of 15 are living with HIV.

"The Church plays a critical role in the provision of HIV treatment, care and support in Africa," Daniel Bekele, executive director of HRW's African Division, said, adding that public health experts agree that comprehensive HIV prevention is critical to achieve success in addressing HIV and ending the Aids epidemic.

While condoms are a key part of preventing HIV transmission and are the only available tool for triple protection against HIV, other STIs and unintended pregnancy, "the (Catholic) Church's continued ban on the use of condoms undermines HIV prevention efforts and increases the risk of contracting HIV, including for women and girls," Bekele said.

A UNFPA, WHO and UNAIDS July 2015 study estimated that condoms have averted around 50 million new HIV infections since the onset of the HIV epidemic. The Church's continued ban on the use of condoms undermines HIV prevention efforts and increases the risk of contracting HIV.

Ugandan Catholics and LGBT tolerance

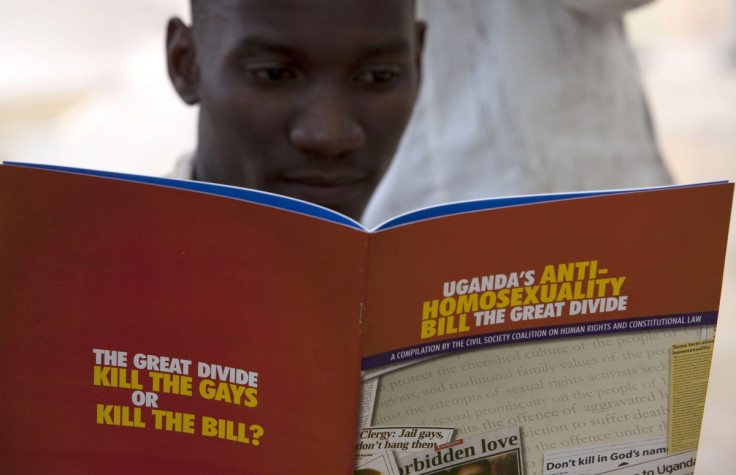

In Uganda, where the Catholics dominate the religiously diverse nation's northern and west Nile regions, gay activists are hoping Pope Francis will preach tolerance toward homosexuals.

In 2014, the country's Catholic bishops reaffirmed their opposition to homosexuality, in a nation where a 2010 survey found that about 27% of the population believes that sacrifices to spirits can protect them from harm.

"Our reaction from the church is very clear, we don't support homosexuality," John Baptist Kauta, secretary-general of the Uganda Episcopal Conference, told Catholic News Service at the time.

However, there was hope as the bishops remained uncertain about an anti-gay bill that included harsh penalties for homosexual acts, including the death penalty. The bill, which was signed into law in February 2014 by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, was later found to be unconstitutional, and nullified in August 2014.

Western opposition to anti-gay measures, however, is often criticized there as "imperialism".

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.