Barclays Cash Transfer Ban Threatens to Plunge Somalia Into 'Chaos'

Millions of Somalis will have a vital financial lifeline cut off by Barclays' decision to freeze money transfers to the country, claim critics.

Barclays has banned transactions with more than 250 Somalian money transfer companies over fears that funds are being channelled to Islamist terror group Al-Shabaab.

But critics claim that the war-plagued African state will be plunged into chaos by the move, with an estimated 40% of Somalis relying on the $1.3 billion (£850 million) wired from relatives abroad every year.

"Millions of people depend on the remittances from outside," said Shukri Ismail, one of the founders of Candlelight, a nonprofit in the northern region of Somaliland told the New York Times. "If those remittances stop, it will be literally chaos."

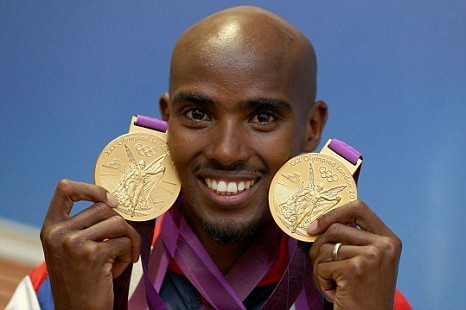

Olympic gold medallist Mo Farah, who was born in Somalia, has added his voice to calls for the British government to intervene and for Barclays to reconsider.

"Everyone following the issue understands that Barclays has a bank to run, but this decision could mean life or death to millions of Somalis," Farah said.

The British government is "looking to really back the new government of Somalia with one hand, and the unintended consequences of these regulations is you could throw a lot more people into crisis," said Ed Pomfret, Oxfam's policy manager for Somalia.

Last year, HSBC was hit with a $1.9bn fine by US regulators for allowing terrorists and Mexican drug cartels to launder money.

A recent UN report claims that money was wired through one of Somalia's biggest money transfer companies, Dahabshiil, to Al Shabaab to fund a plan to assassinate top government officials.

The US recently suspended millions of dollars of aid to Somalia over fears that contractors hired by the UN were channelling money to the terror group.

But after decades of conflict, Somalia does not have a functioning banking system, and experts fear that money transfers will now be driven underground, making it more difficult to track and cut off money to fund terrorism.

"The alternative is bulk cash smuggling, carrying suitcases of cash across the border from other places," Jonathan Schanzer, the vice president for research at the Foundation for Defence of Democracies and a former terrorism finance analyst at the United States Treasury, told the New York Times.

Rushanara Ali, UK shadow international development minister and MP for Bethnal Green and Bow, told the Guardian: "Countries across Africa and Asia will be badly affected and none more so than Somalia, a population reliant on what their friends and families send. Barclays' decision will indeed cost lives - quite apart from potentially triggering a new crisis in the region.

"Shutting this vital lifeline risks giving people no other choice but to send money through dangerous and alternative methods out of desperation.

"We've not heard a whisper from the foreign secretary on this issue. He ought to step in. Barclays' decision risks undoing the fragile progress that has been made after decades of conflict, not to mention humanitarian emergencies, piracy and terrorism," said Ali.

In a statement, Barclays said: "Some money-service businesses don't have the necessary checks in place to spot criminal activity with the degree of confidence required by the regulatory environment under which Barclays operates. Abuse of their services can have significant negative consequences for society and for us as their bank. We remain happy to serve companies who, in our opinion, have sufficiently strong anti-financial crime controls and who meet our amended eligibility criteria.

"We have been engaging with the UK Government, remittance industry bodies and other stakeholders to discuss the issues."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.