2015 election polling fail: Tory voters weren't shy, just 'too busy' to speak to pollsters

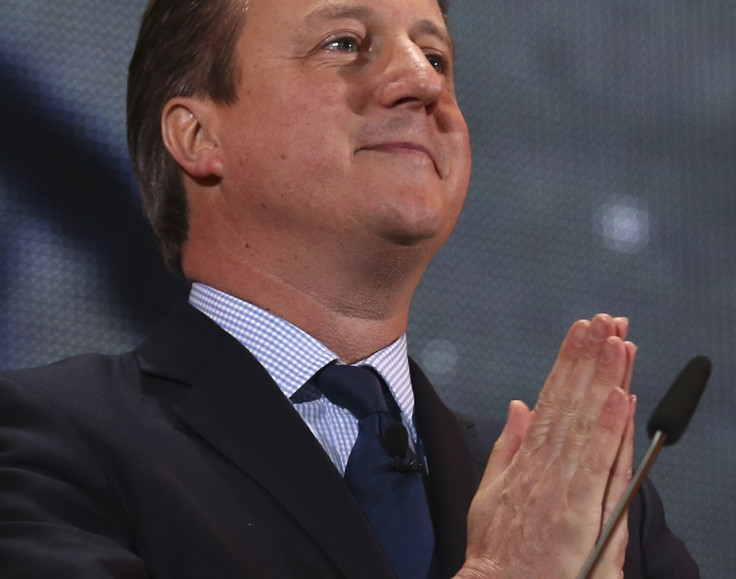

When the Conservatives secured their first majority in nearly two decades at the 2015 general election, it came as a shock to many because the pollsters had for months been saying it was a tight race likely to produce a hung parliament. Questions remain over what happened.

But a new report by NatCen, a non-profit polling firm, claims to shed light on why surveys overstated the Labour party's support ahead of the election. One of the main reasons is simple: Labour voters were easier to contact in the two-to-three days window most pollsters had to conduct their surveys than Conservative ones, who took longer to reach.

NatCen, which conducts the British Social Attitudes (BSA) research, said it found the election result easier to replicate than other pollsters because it took months to carry out its surveys rather than a handful of days. Its researchers were therefore much more likely to pick up Conservative voters, some of whom needed six attempts before contact was made.

The NatCen report found that "those who were the most accessible for interview, that is they were interviewed the first time an interviewer called, were markedly more Labour and less Conservative in their sympathies than were even those who were interviewed on the second call, let alone those who were only interviewed after between three and six calls."

It also said other pollsters did not predict accurately enough who would and would not turnout at the vote. In particular, too much weighting was given to younger voters, who are much more likely to support Labour than the Conservatives, but also less likely than others to actually vote.

"A key lesson of the difficulties faced by the polls in the 2015 general election is that surveys not only need to ask the right questions but also the right people," said Professor John Curtice, senior research fellow at NatCen and author of the report. "The polls evidently came up short in that respect in 2015."

Anthony Wells, director of political and social opinion polling at YouGov, defended pollsters on his UK Polling Report blog at the end of 2015, a year he said "is unlikely to be remembered as a high point in opinion polling".

"Polling is seen as being all about prediction – however often we echo Bob Worcester's old maxim of a poll being a snapshot, the public and the media treat them as predictors, and we pollsters as some sort of modern-day augur," Wells wrote. "It isn't, polling isn't about prediction, it's about measurement. Obviously there is a skill in interpreting what you have measured, and in measuring the right things in the first place, but ultimately the irreducible core of a poll is just asking people questions, and doing it in a controlled, quantifiable, representative way."

He added: "Anyone saying all polls are wrong or they'll never believe a poll again is essentially saying it is impossible to find out how people will vote by asking them. It may be harder than you'd think, it may face challenges from declining response rates, but there's no obviously better way of finding the information out."

A report into what happened ahead of the 2015 general election is due from the British Polling Council, which represents the industry.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.