The bulls in China's eShop: The investor stampede for the next Alibaba

Investors are looking for a toehold in China's 'digital life' where social messaging has melded with commerce at seemingly infinite scale.

Near the top of a glittering tower in down town Beijing, a room full of investment-hungry startups listen as a Chinese venture capitalist tells of how his investment firm turned down a young entrepreneur looking for early stage funding for his ecommerce website, Alibaba.

Some of the startup men - technology insiders, Silicon Valley veterans, Stamford MBAs - want to know more about this cataclysmically bad decision; others marvel at the sheer contingency of success.

York Chen, managing partner, iD TechVentures explains that the final decision was reached by an investment committee, with members in Silicon Valley and India. "They never met Ma," says Chen. "They didn't hear his pitch. They never looked in his eyes."

There's a lot of greed in the room. The men are on an intensive week-long programme aimed at clinching Chinese investment, run by the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (which boasts Jack Ma among its alumni). As well as pitching to VCs, the Westerners will tour the headquarters of Alibaba, Tencent, JD.com and other big platforms.

They are looking for a toehold in China's 'digital life', a new world where social messaging has virally melded with commerce at seemingly infinite scale.

China's obsession with mobile phone apps is part of a larger process of change; since opening its doors to profitable harmony China has been swept by wave after wave of new ideas or "fevers" - learning English, internet dating, the philosophy of Jean Paul Sartre, and the now the ubiquitous WeChat.

"You have to be bold. It's not so good to ask for only a little bit of money. Don't be afraid to ask for a lot. Remember, this is China."

That China will soon overtake America to become the largest economic power on the planet isn't in any doubt. Thanks to the 2008 "Western" financial crises, China accelerated past a historic inflexion point that saw the developing world hold more foreign currency reserves than the developed world.

Then, when China's exports began to shrink, it looked inward and started building. More concrete was poured between 2010 and 2013 in China than by the United States in the entire twentieth century. Real estate has been a favourite investment among China's growing middle class and its price has more than quadrupled in the past decade.

As wealth grows in China so does the need to diversify. Exposure to young technology companies is an attractive option (startup valuations tend to be higher in China than the US) with venture capital syndicates and platforms springing up. China has a reputation for imitation rather than innovation and buying up technology is not a new strategy; within the fast-growing internet arena this approach has been called a "formula for billionaires".

But China is now looking to grow its relatively tiny share of IP and R&D, and to help realise this the Chinese government is rumoured to be disbursing a collection of startup funds larger than the GDP of Denmark. In a sense we have already come full circle, because today Western internet companies are trying to emulate China's digital platforms.

"Everyone is copying what WeChat is doing"

Technology analyst Richard Windsor of Radio Free Mobile points out: "If you look at Facebook, Microsoft, Google, they all have a developer day, and talk about what they are developing on their platform and where they think things are going. What you basically find is that everyone is talking about expanding chat to do other things. So everyone is copying what WeChat is doing."

There is simply nothing close Tencent's WeChat Pay in the West. It has enabled Chinese people to eschew cash, cheques or bank wires, in favour of a new type of digital money. Replacing retail bank accounts with mobile apps was only the beginning.

These apps can be used to pay utilities, any sort of transportation, donate to charity or split bills. They offer access to large pooled saving funds with ten times better interest than banks; they offer investment products and wealth management products and can be used to invest directly in the stock market - all seamlessly and instantly from a mobile phone.

Businesses of every size, from conglomerate retailers all the way down to the guy with the stall selling food, take mobile app payments using scanned QR codes. That's what's happening inside China.

Meanwhile Alibaba aims to rule the world with ecommerce. It's busy taking over other Asian markets, consolidating and reorganising logistics abroad just like it did in China, with a focus firmly on other places with very large emerging middle-classes like India and Africa.

As well as officially growing its global ecommerce trade with AliExpress, there's a rather more subtle strategy underway to seed affluent overseas markets with Alipay by enticing large retailers like Macy's and Bloomingdale's on to the platform.

"Once you have basically got the buyers and the sellers both using Alipay, it's much easier for them to come in with an e-commerce solution that fully supports Alipay. I think that's what their overseas strategy is," said Windsor.

The digital revolution

If the first industrial revolution was organised around factories and access to resources like coal, this current revolution is platform-based. As well as inviting other businesses on to their platforms, the Chinese giants have shown us how to explode into every conceivable vertical.

This is China's own style of aggressive and unstoppable innovation. Leapfrogging fixed-line computing into a world of mobile, where devices come to the consumer neutral of Apple iOS or Google Android, where everybody uses everything, has placed China years ahead of Silicon Valley.

The assumption has been that China will become more Westernised as it rises to dominance, but its platform hegemony could be the beginning of a new technological discourse, what the historian Martin Jacques calls "contested modernity".

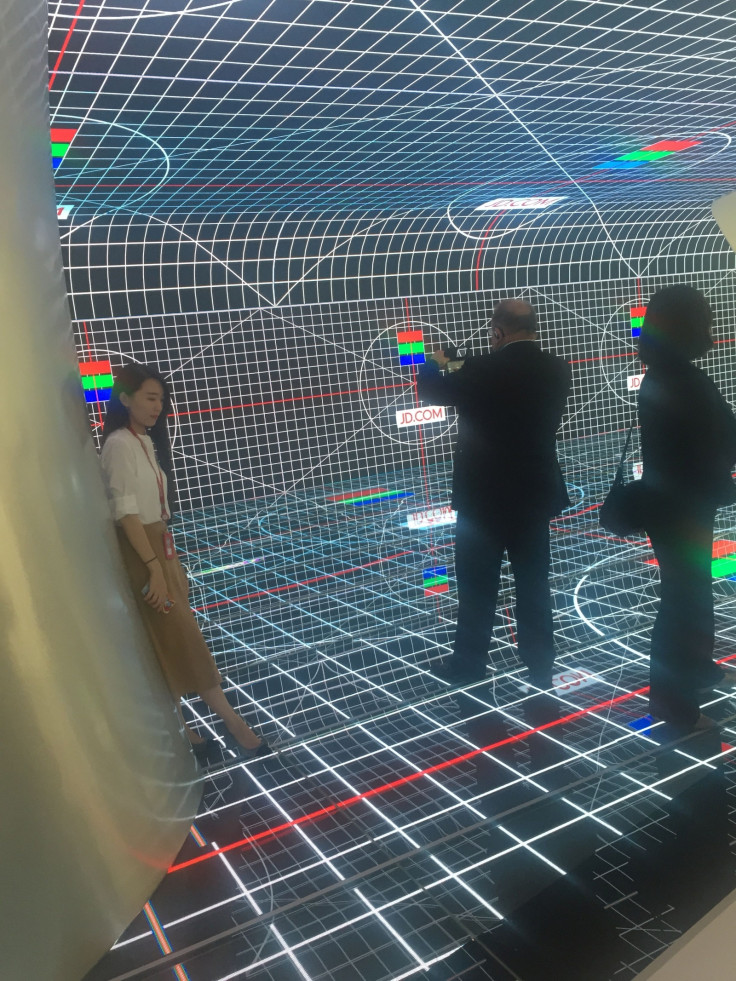

On the outskirts of Beijing in an industrial park about the size of the London borough of Hackney, the entrepreneurs gawk queasily as the walls, floor and ceiling of a digital grotto spring to life and animate an enormous spacecraft doing interplanetary package deliveries. It's the headquarters of JD.com, an ecommerce site competing with Alibaba for the more brand-conscious consumer.

Branded and luxury goods are a big deal in counterfeit-happy China, although there was a 5% slump in demand for brands like Burberry following a recent clampdown on bribery among government officials.

JD.com takes logistics seriously. Its legion of delivery vans constantly circulating in Chinese cities measure delivery times in hours rather than days; JD's record delivery time stands at seven minutes.

Bruce Yang, JD.com director of investment and strategy, is clearly proud of its crowdsourcing delivery platform. "We pay our delivery people well. They receive more than the average graduate – RMB 5000 (£577) per month. China is different from developed countries. We didn't really have logistics systems so we had to build our own. Today they are much better than before."

Chinese ecommerce, which has only reached 15% penetration, is expected to reach $1 trillion by 2018. Like the other platforms, JD.com is moving fast into cloud computing, big data, artificial intelligence and Internet of Things hubs to connect smart homes to video, audio, refrigerators and even beds, via mobile and voice recognition.

A 300kph bullet train from Beijing takes the group south to Hangzhou, the home of Alibaba. The entrepreneurs are led into a boardroom like a small cinema, where one wall becomes a giant, real time, quantitative dashboard, showing points around the globe lighting up and connecting as numbers increase at a bewildering pace: 25,689,089 packages delivered in last 24 hours.

Champion of the small businesses which operate on its platform, Alibaba's philosophy is customer first, employees second, stakeholders third. The digital board dissolves into a film clip about a lotus root farmer joining Taobao, Alibaba's B2B marketplace. The clip ends with the man and his wife and young child laughing together on the balcony of a condominium. "Farmers are happy," says a strapline.

After the clip, Bruce Qian (Bruce is a popular Western alias in China for obvious reasons), senior business development manager, Alibaba, says: "It is Jack Ma's vision to one day do this in every country. The asset is the customer base. If we can make these people successful, then that is also our success."

Next stop is the technology boom town of Shenzhen, where the entrepreneurs are taken to the booming Tencent tower. A Chinese lady from the marketing side of the business paces around and talks quickly while an interpreter tries to keep up.

"WeChat is a new lifestyle," says the translator. The Tencent lady shakes her phone. This invites location-based marketing messages (discount coupons) into the WeChat app.

'But don't Chinese consumers care about privacy and getting spammed?' ask the entrepreneurs. After some conflab the translator comes back with a one word answer: "no".

Back on the bus the startups are practising for their next round of pitching. The conversation returns to the hapless VC who turned down Jack Ma. Holding the mic is CKGSB China Start programme director Bo Ji. He points out that investors from Japan's Softbank knew within five minutes of meeting Ma that they would fund his company; they experienced first-hand the famous Jack Magic.

Turning to the entrepreneurs, Mr Ji advises: "You have to be bold. It's not so good to ask for only a little bit of money. Don't be afraid to ask for a lot. Remember, this is China."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.