Dead Rising: How Capcom's zombie spoof started an open world pandemic

Looking back at Capcom's beloved open world game and how its influenced releases since.

Dead Rising remains the purest distillation of the problem with all sandbox games: there is simply too much of it. Between its two core premises – a world full of zombies and wild weapons, and a complex story players must complete inside a time limit – the game, like flesh bitten from a forearm, is ripped apart.

The originator of Capcom's non-Resident Evil zombie series certainly has a legacy, but as dismal open-world games are churned out for modern day consoles, it looks increasingly dubious. Ten years later, Dead Rising threatens to make slouching idiots of us all.

Moment to moment, it's a wonderful game, filled with colour and fuelled by the evident zeal of its creators. With Resident Evil 4, Capcom had escaped the fixed camera, slow horror confines of its defining zombie series. Two years later, in 2006, the studio flaunted its liberation – loaded with quests, customisation options, weapons, enemies and toys, Dead Rising was one of the first true sandbox games of what was then the new console generation.

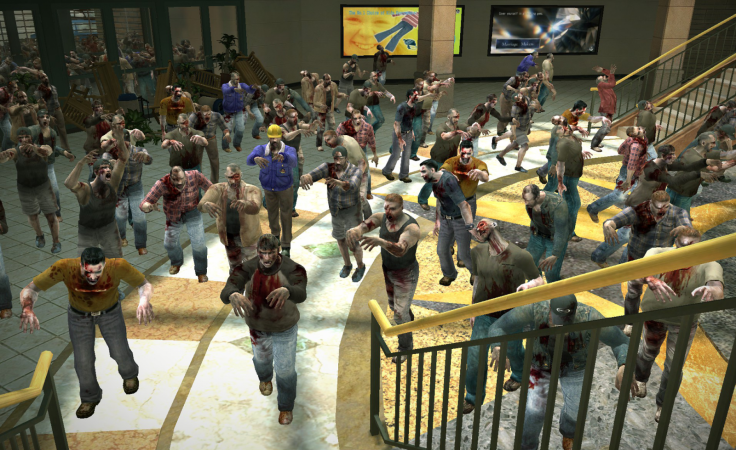

It played, like so many successful games do, to the daydreams of adolescents. Who didn't sit in school planning how they would survive a zombie outbreak? Who didn't watch George Romero's Dawn of the Dead and think 'that looks like fun'? Resident Evil: Outbreak had promised a bigger, more malleable zombie survival simulation, where your choices would determine who lived and died. But under the weight of the PS2's choppy Network and the stale RE series model, it collapsed. Dead Rising, however, was the real deal. Where every zombie apocalypse mod for Grand Theft Auto had felt ragged, Dead Rising was whole, and effortlessly convincing.

It was a progenitor, also, for how contemporary games and their players regard environments and images. The opening of Dead Rising has players, from the vantage point of a helicopter, taking photographs of a zombie-infested town below. Throughout the rest of the game players earn points by framing and capturing quality pictures. A shot of a crowd of zombies eating some poor survivor against a colourful, sometimes humorous, backdrop, will help the player to quickly level up and improve their character.

It was primitive and artificial – admire our level design and get a reward! - but Dead Rising asked players to occasionally stop what they were doing and look around. It promised, in return for such rumination, increased enjoyment. Today, there are dozens of games built entirely upon that premise. Everybody's Gone to the Rapture, No Man's Sky, Proteus, Adrift and a lot more invite players to look rather than do, and find ways to make that simple act of observing a video game in and of itself.

It is common now for stories to be told through scenery, collected artefacts and other ambient means. Dead Rising, with its in-game camera, was a prod towards the BioShock, Gone Home and Fallout form of narrative. Definitively, it told players it was good to just look around.

And yet it is difficult, today, not to view Dead Rising as the harbinger of other, ugly modern video game tropes. Like Saints Row, which would follow it shortly, and its own sequels, Dead Rising is one of the games that led developers, critics and players to wrongly conflate "moronic" and "entertaining." Just Cause 3, Grand Theft Auto 5 and other modern sandboxes, instead of intelligent and meaningful distraction or narrative gravitas, now pursue outlandish, low-brow slapstick. Saints Row is "fun" because you can hit pedestrians with a dildo. Grand Theft Auto is "fun" because you can strip to your underwear and do diving head butts into people. Just Cause is "fun" because you can blow everything up. There are no right and wrong ways for sandbox games to be, but a specific, formal model of the open world persists, relentlessly, and it's rooted in the narrow definition of "fun" that Dead Rising, with its predilection for absurdity and toys, helped carry into a new generation of game-making.

It's also meaninglessly violent (the bloodshed isn't satisfying even in the basest sense) and constantly being pulled between plot and experience. It wasn't the first open-world game to suffer from lack of a discernible identity, but, again, as a flag bearer for sandboxes going into the seventh console generation, one can't help but trace the narrative problems in games like Red Dead Redemption and Assassin's Creed back to Dead Rising. Just what are you supposed to do? Using its trinkets and toys the game invites you to splash around. On the contrary, it's determined to pull you out of the water. A time limit underscores not just every mission but the entire game, meaning Dead Rising's story always gets in front of its playfulness. It's a game – like almost every modern sandbox – where what you do gets in the way of what your character is supposed to be doing, and vice-versa. Ten years later, Dead Rising endures as one of the most prominent examples of how writing and raw, unbridled play do not mix.

Like a zombie virus, its faults have spread, generating a pandemic of confused, contradictory, ultimately unfulfilling open-world games, which seem to be judged only on their capacity to accommodate players' impulses. The reanimated corpse of our closest friend, shuffling toward us, arms outstretched, as we obliviously try to make conversation. Dead Rising, in 2006, was a monster we failed to recognise.

The 10th anniversary remasters of Dead Rising, Dead Rising 2 and Dead Rising 3 (sold separately) are out now on PS4 and Xbox One. The original is also out on PC.

For all the latest video game news follow us on Twitter @IBTGamesUK.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.