How an upcoming vote in Hungary could silence government critics - and see the EU become more like Russia

Human rights groups warned the move will lead to a chilling effect on civil society.

A war of words between human rights campaigners and Hungary's right-wing government is set to come to a head on Tuesday (13 June) as a new "Russian-style" law on non-governmental organisations (NGOs) is put to the vote.

Prime Minister Viktor Orban has been accused of trying to silence his critics by demanding NGOs backed by money from abroad re-register as foreign agents.

Mimicking moves taken by Vladimir Putin in Russia, NGOs receiving more than €23,000 (£19,900) a year from foreign sources will have to identify to the public as an "organisation receiving foreign funding".

They will also have to disclose a list of foreign donors and be subject to further bureaucratic checks.

Orban, who has become a thorn in the side of the EU since beginning his march towards a so-called "illiberal democracy", says the measures are needed to stop foreign meddling in the country's politics.

"Hungary cannot afford to allow organisations that remain in the shadows – not declaring who they receive their money from and for what purposes," Orban said in a radio address in February.

His Fidesz Party government also claims foreign-backed NGOs lack "democratic legitimacy" and are prone to money laundering.

But several human rights groups speaking with IBTimes UK have warned the move will lead to their campaigners being unfairly stigmatised and will have a chilling effect on civil society – one of the last free and critical voices they say is left in Hungary.

Goran Buldioski, director of the Open Society Initiative for Europe (OSIFE), which provides about €4m to around 50 NGOs in Hungary every year, even suggests Orban's crackdown could spark a contagion, as other EU leaders eager to silence their critics do the same.

"It creates a precedent where other leaders – in particular Slovakia, Romania, Poland, to list just a few – may follow suit because they could see this as establishing a certain control of sovereignty in their countries," Buldioski tells IBTimes UK from his office in Hungary's capital, Budapest.

"My worry is first contagion – that the civil society space will shrink and will not be as open as it were. But I also have an additional worry. Today it's civil society – will other entities be next?"

He added: "There have been attacks for the past three years [on] different sets of civil society organisations [in Hungary].

"If you're an independent organisation that wants to spell out the things clearly, and that means sometimes complimenting the government but also often criticising, you will be under attack by the government and probably the subject of a smear campaign.

"This is not how I believe a healthy society should develop."

Open Society has found itself centre stage in the row over the proposed NGO law.

Orban's chief villain in his battle to supposedly protect Hungary from menacing outsiders – a tactic he used in the peak of the migrant crisis to popular effect – is the group's founder, Hungarian-born billionaire George Soros.

"The following year will be about the squeezing out of Soros and the powers that symbolise him," Orban said in December. Szilard Nemeth, vice-president of the ruling Fidesz party, went further, calling for Soros-backed NGOs to be "swept out" of Hungary.

Soros grew up under Nazi occupation and later communism, before he left Hungary and eventually settled in the US. A financier with deep pockets, Open Society says he has since donated more than $12bn to help protect his country and others from authoritarianism.

But Orban, who gained prominence nationally with his fight to rid Hungary of Soviet troops while in his mid-20s, tells his country's people and its increasingly-regulated media a different story.

Soros, the Hungarian leader says, is a shadowy financier, an enemy of the people; he pulls the strings of Hungary's liberal NGOs as they try to prevent a democratically-elected government from pursuing the will of the people.

This includes, Orban says, his policies against immigration – strongly criticised by the EU and United Nations, but popular domestically – and laws further regulating the media and judiciary.

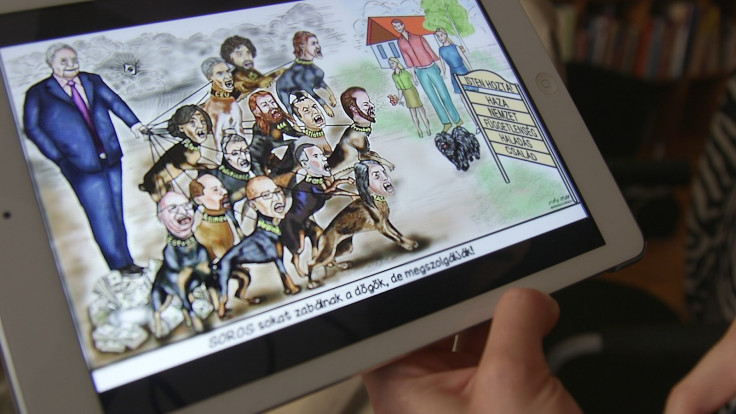

It's a caricature epitomised by a not-so-subtle cartoon recently printed in one of the country's right-wing publications and shared among Orban supporters online.

It shows a sneering Soros holding the leashes to a pack of vicious dogs as they bark at a wholesome-looking Hungarian family. Each frothing animal has the face of an NGO leader said to be an enemy of the country.

One of those dogs is supposed to represent Patent, a Hungarian women's rights group part-funded by Open Society that specialises in helping female victims of violence.

Far from the all-powerful enemy Orban's supporters suggest exist, the group's volunteers operate out of a tiny Budapest office tucked away in an apartment block south of the River Danube.

They tell IBTimes UK that even without the proposed law, life for NGOs in Hungary has become tougher – and that the impact on the women they help could be devastating.

"I have a big fear of the main women's NGOs disappearing because they face not only government bullying, but also a disappearing of funding," says Noa Nogradi, a volunteer communications officer for Patent.

"We have less and less resources, and less and less energy – and we're constantly being bullied. It's very hard to keep up our work, and I think our work is very, very important. If we don't do it, then there's nothing.

"There are so many women who always give us feedback that 'if you weren't there then there would have been nowhere I could have turned'.

"I'm quite scared about what will happen to us in that sense."

Patent is one of dozens of NGOs keeping a concerned eye on how next week's vote could change the civil landscape of their country. Their work includes protecting minority groups, helping refugees, promoting democracy and defending an independent media.

Amnesty International has strongly urged Orban's government to U-turn, saying the proposed law represents an "ominous blueprint for the oncoming assault on Hungarian civil society ... discrediting and intimidating NGOs and undermining their capacity to protect human rights and provide valuable services to Hungarian people".

Add to that strong criticism from the Soros-backed Hungarian Civil Liberties Union – which claims the proposed law violates EU and international legislation – and anti-corruption charity Transparency International.

The row has also dragged in senior EU politicians, who fear Orban is taking his country away from Brussels and towards Putin.

In extraordinary scenes in the European Parliament in April, Orban was rounded on by critics who accused him of turning his back on democratic principles with his attacks on civil society, migrants and the media.

"Harassing NGOs, chasing away critical media, building walls ... How far will go you? What is the next thing? Burning books on the place before the parliament in Hungary?" asked a fuming Guy Verhofstadt, the European Parliament's chief Brexit negotiator.

But Orban responds to his critics with a familiar message: his policies have popular support at home and Brussels tries to "tell Hungarians what to do".

It's a view he tries to back up with the results of questionnaires sent to households across his country asking their opinions on various government proposals. Critics say the surveys – the most recent titled "Let's stop Brussels" – are biased, misleading and often factually incorrect.

Whether a true believer or a political opportunist, Orban sees next week's vote on the NGO law as just another step towards delivering his vision for an "illiberal democracy" in Hungary.

Since being elected with a two-thirds majority in 2010, his government has cemented its power by rewriting the constitution and passing a swathe of new laws.

But opponents fear the worst is yet to come, with Orban and his supporters buoyed by the election of Trump – another politician who campaigns on anti-liberal platforms, and another staunch opponent of Soros.

If the growing row between Brussels and Budapest has highlighted anything, it's the EU's limited options for clamping down on those member states which fail to uphold democratic standards.

The Venice Commission, an advisory body of the Council of Europe (the continent's main human rights organisation), has already raised concerns about the proposed NGO rules, saying they could "adversely affect their legitimate activities and may raise a concern of discriminatory treatment".

While distracted by various financial crises, the spread of right-wing populism and Brexit, how Brussels responds to the outcome of next week's vote could be a key moment in the future direction of the EU.

As Buldioski warns: "Hungary is not Russia. Hungary is a full member of the European Union, and European Union's key premise is rule of law."

Orban's critics fear if his government is allowed to continue its crackdown on NGOs, it may well become like Russia.

The Hungarian government did not respond to a request for a comment by IBTimes UK.

Orban's government often justifies its policies by saying they have the popular domestic support. It uses the results of questionnaires sent to households as proof. But critics say the questions are biased, misleading and inaccurate.

This is the question sent to Hungarians in April 2017 asking their opinion on the NGO law (source: Hungarian Civil Liberties Union).

More and more foreign-supported organisations operate in Hungary with the aim of meddling in the internal affairs of our country in an opaque manner. Their operations could jeopardise our independence. What do you think Hungary should do?

(a) Require them to register, revealing the objectives of their activities and the country or organisation instructing them.

(b) Allow them to continue their risky activities unsupervised."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.