Margareta Pagano: Sir Owen Green and Fidelity lead 'greed isn't good' boardroom pay crackdown

Almost 12 years ago to the day, Sir Owen Green, who had just retired as chairman of Britain's highly successful BTR conglomerate, launched the most devastating attack on the excesses of boardroom pay.

His attack – published by the Daily Mail – was all the more pertinent because it came from such a highly regarded industrialist and blue-blooded capitalist who had built up BTR by buying under-performing companies and turning them around. Some described him as an asset-stripper; others as entrepreneurial.

Yet Green, a gentle man by nature, was incensed by the culture of greed that he watched sweep through British boardrooms in the 1990s and the newfangled fashion for complex share-options structures including long-term incentives plans that were blowing fast and furious from across the Atlantic.

He thought these new pay rewards for CEOs and their executives of publicly listed companies were deeply unfair, dangerous for society as a whole and a searing indictment on the lack of leadership among Britain's industrialists.

This is what he wrote at the time: "How a director who has just had an 18% rise dare tell his workers to show restraint and accept less than 5%, I cannot understand... Can you work wholeheartedly for a company which accepts that sort of behaviour at the top?

"I wonder how many of them honestly believe they are worth that money. For these people are neither show business stars nor entrepreneurs... They are doing normal jobs, albeit at a high level, and they are all replaceable." Those same words would not look out of place today.

Shortly after his outburst, I interviewed Green for BBC current affairs programme Newsnight and he was unequivocal that the only way to curb such rewards was public shame. As he said, the City was unlikely to take action as everyone involved in the pay game stood to benefit: the so-called remuneration experts advising companies, the headhunters, the fund managers and the non-executive directors sitting on the remuneration committees of the companies in question.

Attempts to cut excessive rewards have come and gone

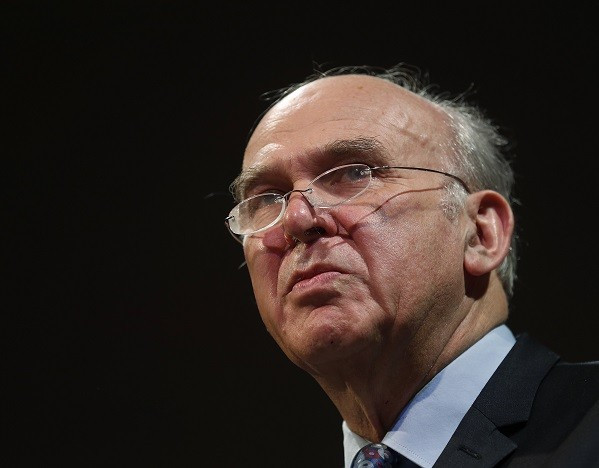

Since then there have been many attempts, most of them lily livered, at trying to cut down on some of the more extreme rewards, particularly for golden goodbyes. When he was business secretary, Vince Cable introduced binding votes on shareholders to try and curb the worst excesses.

There has been some success: during the "shareholder spring" three years ago, the bosses of Trinity Mirror and Aviva lost their jobs after pay revolts by investors. More recently, shareholders have been flexing their muscles at Deutsche Bank, Man Group, BG, RSA and Alliance Trust.

Overall, though, pay for FTSE bosses just keeps on climbing. The average salary package today is £5m for a FTSE 100 CEO compared with £1m 15 years ago. That means the top directors are earning several thousand times the average wage – at a time when average wages have been in decline. Plato, who suggested no man should earn more than four times that of another, would not have approved.

Cracking the pay culture has taken far longer than Green hoped for but his point about shame may now at last be filtering through to the industry itself.

According to new reports, the Investment Association, the trade body whose members invest between them some £5tn of assets, is holding private talks with its fund managers to look at how it can control soaring pay at the companies it invests in.

More critically, the fund managers are said to be specifically looking at ways to simplify and also block the abuse of long-term incentive plans, known as L-tips.

One of the few more outspoken critics of runaway pay is Dominic Rossi, global chief investment officer of equities at Fidelity Worldwide Investments, who wants companies to insist on longer periods before the L-tip share awards vest. As Rossi points out, executives are allowed to sell their shares when they have been vested for three years; hardly a long-term plan.

Rossi has been sticking to his guns, telling companies in which he invests that Fidelity will vote against all awards unless they are run for the full five years. It has been one of the most active of stubborn investors, voting against the remuneration of 56% of the companies that have held their annual meetings so far in 2015.

Hopefully, Rossi will continue with his campaign and make sure his sensible views are top of the agenda when the Investment Association members meet next to continue their debate and, dare one say, take some action. No doubt company directors and their advisers will try to bite back, arguing such share awards are the most effective way of aligning their pay with the interests of shareholders.

They should treat this as tosh. Another of the UK's wisest industrialists, Sir Nigel Rudd, has the best answer. He says there is a simple way to align the performance of a boss with that of his or her company and its workers: let them buy their own shares in the market with their own money.

Margareta Pagano is a business journalist who writes for the Independent and the Financial News. Follow her on Twitter @maggiepagano.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.