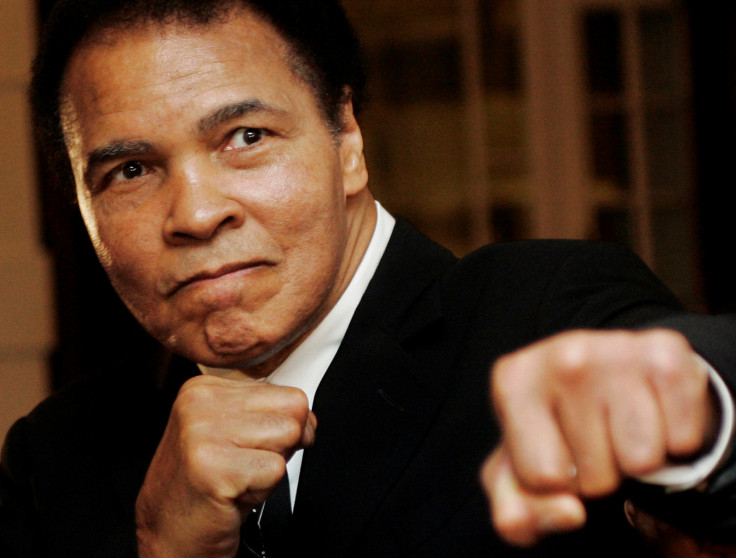

Muhammad Ali: A heavweight hero who was more loved by the world than by America

A year ago my daughter and I visited the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville, Kentucky. I'd always loved Ali as a kid. As an eight-year-old I watched the Rumble in the Jungle with my Grandad – probably a day later, quite probably without knowing the result yet: It was a different world.

It was an incredible fight: the 32-year-old seemingly being battered into submission by George Foreman, until the younger boxer had punched himself out and Ali swiftly and decisively turned the tables. (The film about it, When We Were Kings, is a thoroughly deserving tribute).

Ali burst further into our generation's consciousness in England with his Michael Parkinson interviews (back in the day when 10 million people watched the same prime time TV shows). He was fantastically entertaining as a speaker as well as a skipping, dancing, delight of a boxer.

Ali remained an inspirational figure through great fights and into his later life. But it wasn't until I visited the Ali Center that I truly understood and appreciated the scale of his importance in the Civil Rights era: a proud, confident, charismatic black man who won Olympic Gold for his country and then changed his name because of the racism he encountered in his homeland.

He refused to fight in the Vietnam War long before everybody else realized what a disastrously ill-advised conflict that was. His stance was purely principled and as eloquent as he always was before the Parkinsons took control:

"I ain't draft dodging. I ain't burning no flag. I ain't running to Canada. I'm staying right here. You want to send me to jail? Fine, you go right ahead. I've been in jail for 400 years. I could be there for four or five more, but I ain't going no 10,000 miles to help murder and kill other poor people. If I want to die, I'll die right here, right now, fighting you, if I want to die. You my enemy, not no Chinese, no Vietcong, no Japanese. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice."

Ali lost the best three years of his boxing career (and his world titles) because he refused to go and kill his non-white brothers. He came back and won the title anyway. He once fought Ken Norton – back in the days when there were a lot of very good heavyweight boxers – for 12 rounds having had his jaw broken early in the bout. He lost the world heavyweight title a second time – this time in the ring – before claiming it for an unprecedented third time.

Where I had always assumed everyone loved Ali because he was "The Greatest", actually a large proportion of America was far less enamoured. He upset the established order, gave hope and inspiration to millions of black people, and frightened a lot of white racists.

In Louisville there is a small district packed full of museums, featuring, among others, the Ali Center and the Louisville Slugger baseball bat factory. There were noticeably more visitors at the baseball bat museum than at the boxer's awe-inspiring centre, which is tucked around the corner from the main drag museums.

The Ali Center tells a profound story, as much about civil rights as it is about sport. The boxing elements are imaginative and enthralling (you can watch any and all of Ali's fights in video booths or spar in a boxing ring while being trained by Ali's daughter). But just as impactful are the exhibits around his life – and those of millions of other black Americans – facing everyday racism and the brave struggle to overcome those powers and prejudices.

A stroll through the museum takes you through the glory years (his boxing robe donated by Elvis Presley is as gaudy as you would expect) to the inspiration he became in later life despite the debilitating affects of Parkinson's, a disease that was almost certainly linked to the punishment he took in the boxing ring). Even as a frail shadow of his former self he lit up whichever room he was in.

The final exhibit in the Ali Center is a play area with activities designed to promote peace and understanding, a message he shared eloquently.

In Louisville every child (and adult) tourist we saw was carrying a Louisville Slugger museum baseball bat. My daughter didn't want one of those though, she wanted a pair of Ali boxing gloves. She – and I – are very sad today. RIP Muhammad Ali. You were The Greatest.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.