3I/ATLAS X-Ray Images Show What Happens When Interstellar Comet Gases Meet the Sun's Charged Particles

European spacecraft captures rare collision producing red glow

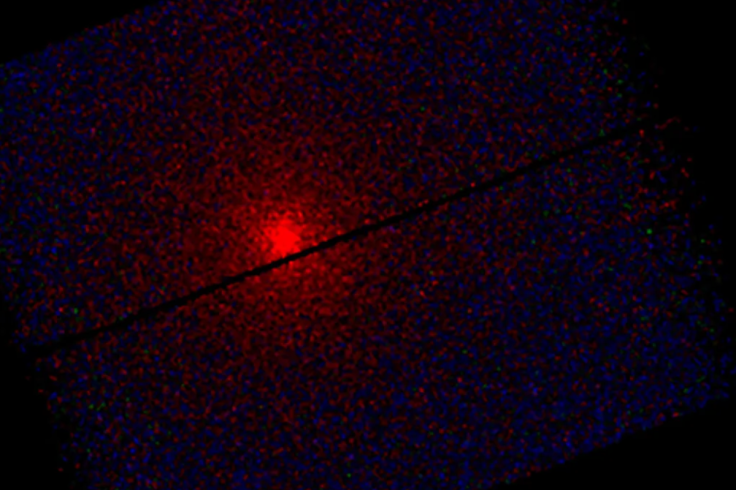

The European Space Agency's XMM-Newton space observatory has captured the first-ever X-ray images of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, revealing a crimson glow against the blackness of space. These observations provide an unprecedented look into the chemical makeup of an object that originated from another star system.

The comet, only the third confirmed interstellar visitor to our solar system, will make its closest approach to Earth on 19 December. It follows the discoveries of 1I/'Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019. Scientists confirm 3I/ATLAS poses no threat, passing at a distance of approximately 168 million miles (270 million kilometres), nearly twice the distance between the Earth and the Sun.

How Solar Wind Makes a Comet Glow

The new images show the comet as a bright red spot. The red colour marks actual X-ray emission captured during a 20-hour observation session on 3 December, when the comet was about 285 million kilometres from the spacecraft.

This glow is created through a process known as 'solar wind charge exchange'. Gas molecules stream from the comet's icy nucleus as it is heated by the Sun. These molecules then collide with the solar wind, a constant stream of charged particles ejected from the Sun. When oxygen ions in the solar wind strike the neutral gas molecules, they steal electrons, enter an 'excited state', and then release X-ray photons as they stabilise.

XMM-Newton's European Photon Imaging Camera captured the event. The image uses colour to show energy levels: red marks low-energy X-rays produced by the collisions, while blue indicates empty space.

Seeing What Other Telescopes Cannot

While the James Webb Space Telescope and NASA's SPHEREx mission have already identified water vapour, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide, X-ray telescopes can detect gases that are otherwise invisible.

Hydrogen and nitrogen do not appear clearly in optical and ultraviolet light, making them difficult for instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope or ESA's Juice mission to observe. X-rays, however, cause them to become visible. This capability is significant because 3I/ATLAS formed around a different star. The X-ray data could help test a prevailing theory that the first interstellar object, 1I/'Oumuamua, might have been composed of exotic ices such as solid nitrogen or hydrogen.

How Solar Wind Makes a Comet Glow

The technical term for the phenomenon is 'solar wind charge exchange'. Gas molecules stream from the comet's icy nucleus as it is heated by the Sun. These molecules then collide with the solar wind, a constant stream of charged particles ejected from the Sun. When oxygen ions in the solar wind strike the neutral gas molecules, they steal electrons, enter an 'excited state', and then release X-ray photons as they stabilise.

Japan's XRISM spacecraft also observed 3I/ATLAS in X-rays between 26 and 28 November, detecting a faint glow stretching approximately 400,000 kilometres around the comet. The combined data from XMM-Newton and XRISM provides the most detailed analysis to date of an interstellar comet's interaction with our Sun's environment. Research in The Astrophysical Journal notes that X-ray observatories provide cometary data impossible to obtain through other means.

Closing Window for Observation

3I/ATLAS makes its closest approach by about 270 million kilometres (168 million miles) to Earth on 19 December. After that date, the window starts closing. The comet will keep moving, getting fainter and harder to observe until eventually it leaves our Solar System completely.

This impending departure is why a massive coordinated push involving observatories all over the world—and in space—is grabbing every bit of data they can whilst they still can. That includes X-ray, ultraviolet, optical, infrared, and radio data. These interstellar objects provide invaluable samples of material from distant star systems that we may never otherwise reach.

🚨 3I/ATLAS Looks Nothing Like a Comet in ESA’s Latest X-ray Image

— All day Astronomy (@forallcurious) December 12, 2025

The latest X-ray image of 3I/ATLAS shows several features that don’t look like a typical comet:

☄️ 1. Spherical Glow, No Tail

Instead of a long comet tail, the X-rays form a compact, almost round glow.

☄️ 2.… pic.twitter.com/WKwTYOlQG7

As scientists work through the data flooding in from multiple observatories, they are building the most complete picture ever of what an interstellar comet is made of and how it behaves. That understanding will reshape our knowledge and understanding of how planets form, not just here but everywhere.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.