Angola's adoption of social media legislation 'may set dangerous precedent for Zimbabwe'

EXCLUSIVE: Zimbabwe could follow Angola's steps to silence social media with legislation.

While Zimbabwe's Parliament is yet to set a date for the examination of a controversial Cybercrime bill, analysts have warned that Angola's adoption of a similar legislation may have set a dangerous precedent for the region. In the wake of growing discontent over the deepening socio-economic problems in Zimbabwe, the government is trying to tighten its grip on cyberspace and social media with the potential introduction of the draft Computer Crime and Cybercrime Bill.

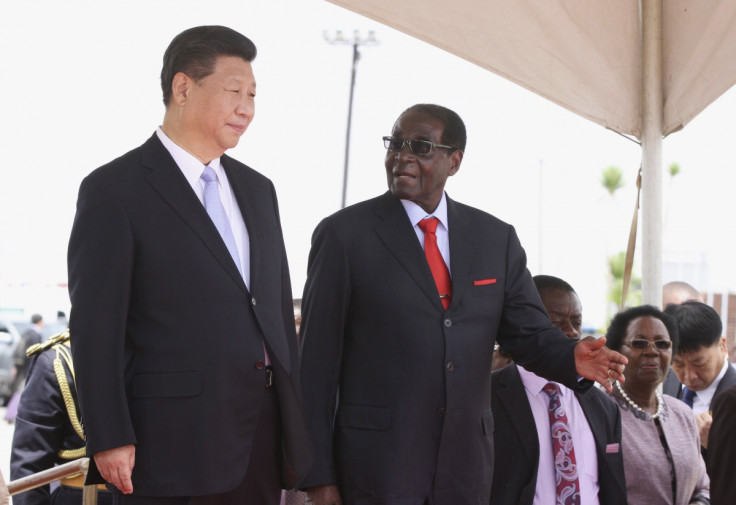

Faced with protests driven by social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter and What'sApp over the last three months, President Robert Mugabe has turned his guns on social media users.

The country's cabinet this week said it had passed the draft National Information Communication Technology (ICT) policy which gives control of all internet gateways and infrastructure to a single company, over which government has control. This will enable the government to monitor, filter or even block specific internet services – including WhatsApp and Twitter.

The ICT policy also sets the tone and direction for three other bills, which include the Cybercrime Bill (see box) that rights groups claim clamps down on citizens' digital rights and prevents hashtag protests.

What does the Computer Crime and Cybercrime Bill provide?

- Effectively enables the government to demand the source of information of any content considered as cybercrime from internet service providers

- According to the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper, the official document states that "any person caught in possession of, generating, sharing or passing on abusive, threatening, subversive or offensive communication messages, including WhatsApp or any other social media messages that may deemed to cause despondency, incite violence, threaten citizens and cause unrest, will be arrested and dealt with accordingly in the national interest"

- Under Section 23 of the draft bill, social media users found guilty of "abusing" the use of the platforms could face five-year prison sentences or a fine, or both

- However, commentators claim, the text is "vague" – meaning the law could be applied in ways that the government sees fit.

Angola's dangerous precedent

Last week, Angola took steps to silence social media with a new regulatory body as part of the ruling party (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, MPLA)'s battle to retain its 40-year grip on power in the face of a growing wave of discontent.

Angola's 2010 constitution guarantees the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and freedom of the media, but under the new rules, a new MPLA-run body – the Angolan Social Communications Regulatory Body (ECRA) – will have total control of media. This is a major concern particularly among human rights activists, campaigners and journalists.

"There is a precedent in the region with Angola, which has faced this problem for years now and these guys watch each other. Whereas (Zimbabwe's ruling party) Zanu-PF has rested on its laurels in the past – maybe because it felt social-media driven discontent was not so much a problem for them – it is something to take something seriously now," warned Blessing-Miles Tendi, who teaches politics in the University of Oxford's Department of International Development.

Zimbabwe and Angola are both member states of the the Southern African Development Community (SADC), along 13 other nations.

"Because Angola's legislation has gone through, Zimbabwe can do it too because, would SADC criticise them for it, they will be able to argue that they are only following the cue from the Angolans. It's not something the opposition and activists can take to the regional body's human rights and democracy tribunal that addresses rights violations among its member states," Tendi exclusively told IBTimes UK.

"Zimbabwe's regime used to dismiss the use of social media for mobilisation in the past, but it has now become very clear that, with an eye to the 2018 election, it wants to clampdown on the social-media driven protests," the professor said.

'Zanu-PF is broke and repression costs money'

President Robert Mugabe's ability to get the legislation through and then apply it, however, has come into question. "The big majority of the Parliament is allied with the president and they control the judges that were all appointed by Robert Mugabe so if they want to make it happen they can, but whether the other MPs will vote it in I'm not so sure," Tendi said. The ruling Zanu-PF party won a two-thirds majority in Parliament in the 2013 elections.

However, the regime is yet to implement the 2013 Constitution, and there is a backlog of legislation before Parliament. "Common sense may prevail and they may look at more important policies to implement rather than fast-tracking this bill," Tendi added.

But acquiring funding for the implementation of intelligent control of softwares and platforms remains the biggest challenge for Mugabe's cash-strapped government. In July, facing a cash shortage, the finance ministry was forced to delay pay for civil servants – including doctors and the military and the authorities have imposed strict limits on the amount that ordinary people can withdraw from bank accounts.

"Repression costs money. When you can't pay your civil servants on time, where do you find the money for it?" Tendi said. The government now needs to pay off $1.8bn (£1.37bn) arrears to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and implement economic reforms if it is to be awarded financial assistance to avoid an economic catastrophe.

"The Zanu-PF government is broke: it's one thing to have these legislations, but there are power cuts all the time and internet is also down – so it will struggle with the practicalities such as importing software from the Chinese – something the Angolans don't face," Tendi said, highlighting that, while Angola's government revenues may have faced recent losses from the oil sector on the back of a halving of oil prices, the regime is busy turning around its sluggish economy.

"The Angolan MPLA actually has oil money to pay for people manning particular forums or softwares to control social media," Tendi explained.

Frayed relations with the Chinese

As Mugabe earlier this year threatened to introduce a Chinese-style internet control apparatus, could funding to implement Zimbabwe's legislation be found through its Chinese counterpart?

A year ago, both governments announced Zimbabwe would benefit from China's $40bn investment but Tendi said he believes plans may have been put on hold as the Asian giant –Zimbabwe's largest source of foreign investment for years – struggles with the enforcement of Zimbabwe's so-called "indigenization" law. The controversial policy requires foreign companies with assets of more than $500,000 to transfer or sell a 51% stake to indigenous Zimbabweans.

Whether or not the indigenization policy is targeted at China, the future of the Sino-Zimbabwe friendship has come under pressure as China voiced its displeasure at the government's plan, particularly in the case of the diamond mining industry. In March 2016, Mugabe accused foreign companies – including Chinese mining firms – of stealing $15bn worth of diamonds.

"Last year, analysts believed that the Chinese may have come in and helped Mugabe fund these processes. But because their relationship is going through a rocky patch at the moment, a number of projects that were supposed to have taken off haven't, and now Harare actually had to turn to the IMF for a bailout package."

Laslty, Tendi explained, implementing a legislation curtailing citizens' digital rights would be "counterproductive" for Zimbabwe's regime whose human rights violations have threatened re-engagement efforts with the Bretton Woods Institution. "Practically, if Mugabe wants to get money from the IMF, it's not a good idea to violate those rights."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.