Fallout 4: Video games love the apocalypse because it makes humans either dead or simple

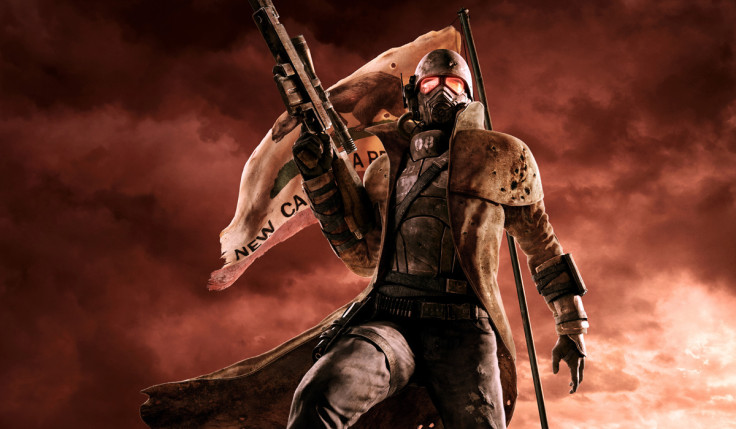

There's a lot of fun you can have visually with the apocalypse - lots of explosions and mutants and desolate landscapes. There's also a lot you can do in the broader creative sense. It's like fantasy or sci-fi – apocalyptic worlds are so removed from our own that you can introduce eccentricities like the clans in Mad Max, the weapons in Fallout, and the monsters in Metro, and no-one will bat an eyelid. The apocalypse is a broad palette. That's why games love it so much.

It's also a convenient sidestep around something video games have long struggled with: human characters. Video games hate people. People are hard to draw and animate. Their complexities and personalities are difficult to capture, doubly so when you're contending with action and gameplay and your writing needs to be brief.

This is why there's so much fantasy, so much sci-fi, so many games where you play a non-human, or a cartoon approximation of a human. Games just don't have the time, or perhaps not the wherewithal, to create credible human characters.

And that's why games love to kill off everybody in the world before they've even begun. In Everybody's Gone to the Rapture you get a pretty, still world to gaze at without any interruption from complicated icky humans, because games have more love for nature and buildings than they do for humans.

In Mad Max, Fallout, Metro and many others, there are human characters, but the direness of the apocalypse situation reduces them, largely, to a singular survival instinct. Their needs, wants and emotions are basic, and easier to write for than complex human personalities. Apocalypse narratives either get rid of people or turn them into animals that are easy to define.

That's not to say video games set in apocalyptic worlds are disregarding of people and human experience on the whole. There's politics in Metro, emotion in The Walking Dead, and humour in Fallout, and these are characteristics of human experience.

But apocalyptic games are still emblematic of that troubling avoidance strategy, whereby the humanity of human characters is downplayed and mitigated. In SOMA you play not a person but a robot with a person's mind. In Everybody's Gone to the Rapture you encounter not people but their ghosts, their memories. In hundreds of games you play a person but one who never speaks, never expresses any feelings and has no personality – a human being in body only.

Video games want to have their cake and eat it. They want to put human beings on screen and claim to be emotional, personal, charismatic, but without having to sacrifice much time or effort to really explore or care about what being human means.

The eponymous New Vegas of Fallout: New Vegas is one of the best symbols of video games' unwillingness, or incapability, to properly do human characters. It's built up throughout the first part of the game as a refuge from the apocalypse, a place that largely survived the nuclear fallout and is now home to casinos, bars, brothels and all sorts of human excess.

Almost anywhere you go in Fallout: New Vegas you can see the titular city on the horizon – it's characterised as a living, happening place, the physical opposite of the dead, dry Mojave Wasteland. But when you get there, the people are all stood ramrod still, doing nothing, saying nothing.

Like everyone in the Fallout world, they feel plastic and robotic. There are vast empty spaces in New Vegas, entire buildings containing maybe two people. It looks and feels nothing like the buzzing human dwelling which the game describes.

It's a technical limitation more than a problem with writing or design – I don't think New Vegas necessarily shows how game-makers try to avoid creating credible human characters, but its layout and graphics make for a good representation of that thing video games do, where they profess to being about people and life experience but in fact are largely inhuman.

New Vegas is built up as perhaps the last remnant of the pre-apocalypse world, the closest thing left to a credible, contemporary human settlement, where people have the luxury of not living like survivalists. But when you get there it's as bleak and bare as anywhere else in Fallout. It doesn't seem like a town, full of people – it's another tired, grubby necropolis. New Vegas is no more alive than the wasteland around it.

And that's what games do with human characters, place them on-screen but represent them in only the barest sense. Like Mr House, the enigmatic patriarch of New Vegas city, who turns out to be a computer program, the human characters in games are fronts and charades, physical bodies, maybe, but never given much personality or complexity.

The writers just can't be bothered. And the general standards people have of video games, that they be action heavy, and that the concept of "mechanics" should always include shooting, climbing, racing, puzzle-solving or exploring, are prohibitive.

I think people can't help but fantasise about the apocalypse because of its inherent sense of abandon – there's a grotesque pleasure in imagining liberation from social and moral confines. Video game designers love the end of the world because it frees them.

Fallout 4 is available for PS4, Xbox One and PC now.

For all the latest video game news follow us on Twitter @IBTGamesUK.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.