Stefan Stern: Money to be made in the 'age of digital' as Accenture and McKinsey lead the charge

Nobody's perfect. Not even a superhero chief executive or an all-conquering board. Managers of the month have the occasional off-day, or week. Few businesses possess all the data they need, or have a clear view of the threats and opportunities they face. They regularly confront situations they have not experienced before.

For all these reasons, and more, we have management consultants. True, their popularity scores sometimes come in only slightly higher up the league table than those of estate agents, politicians and, er, journalists. Business leaders in particular can affect a near-permanent (public) disdain for the idea of buying in advice from consulting firms.

Thus surveys of business sentiment towards consultants tend to produce the opposite problem to that thrown up by equally unreliable surveys of sexual activity: businesses are rude about consultants even though they may use them a lot, while respondents to sex surveys claim to be achieving prodigious levels of activity when in fact... you get the point.

On Monday 15 June, we received a bit more evidence to support the idea that management consultancy, in the UK at least, is alive, well and growing. The Management Consultancies Association (MCA), the industry trade body, released its annual survey of its members' activity. MCA members carry out about 60% of consulting activity in the UK and, according to them, business grew by 8.4% in 2014, taking their annual revenue up to over £5bn.

Businesses in all parts of the economy are making bigger demands on their advisers: financial services, infrastructure, retail, technology and the public sector too (although here, the numbers are still down on the pre-crash years).

The "age of digital" is proving something of a boon to consultants, as industries try to re-engineer themselves to be ready for smartphone-wielding customers. Even strategy, that until recently unfashionable concept, is back as a lucrative business stream: at over £500m, it represents a tenth of MCA members' turnover, up by 44% on the previous year. It's a complicated world and busy people need help.

Consultants are "knowledge brokers", as Professor Andrew Sturdy of Bristol University has put it – not necessarily inventors of new ways of doing things but effective disseminators of emerging (as well as established) ideas. As the world and markets change, an outside view can be useful.

Of course, bigger businesses will gather quite a lot of expertise in-house and have their own strategy teams, foresight groups, scenario planners and so on. But they too cannot know everything and may need to test their thinking with detached observers.

Consultancies are evolving beasts

Consultancies survive in part by taking some of their own medicine or, rather, adopting their own remedies. They change to fit in with changing times. So just as many consulting firms are now recruiting tech experts to provide services in this digital age, in the past they have built teams to offer advice in the latest business ideas, whether it was total quality management, business process re-engineering, just-in-time supply chains and lean manufacturing, and so on.

As Chris McKenna explained in his history of consulting, The World's Newest Profession, so-called "cost accountants" transformed themselves into management consultants when Glass-Steagall legislation in the 1930s meant auditors could no longer offer business advice to their clients.

Legislation created a gap in the market into which they leapt. Walter Kiechel showed in his book, The Lords Of Strategy, that consulting firms have long displayed an entrepreneurial (and opportunistic) genius for reinvention, creating the "strategy" industry when for decades "planning" had been deemed an ambitious enough task.

If the circa £9bn UK consulting industry sounds big, consider the global figure: $245bn, according to Kennedy Research. Not only the big four accounting firms but also the elite bulge trio of McKinsey, Bain and the Boston Consulting Group dominate the international scene. Accenture and Tata Consulting Services figure prominently too.

These big players not only serve global corporations, in mature and emerging markets, but are also sought out by governments, hungry for what they believe will be expertise. The advice may or may not always be brilliant. But it will certainly cost.

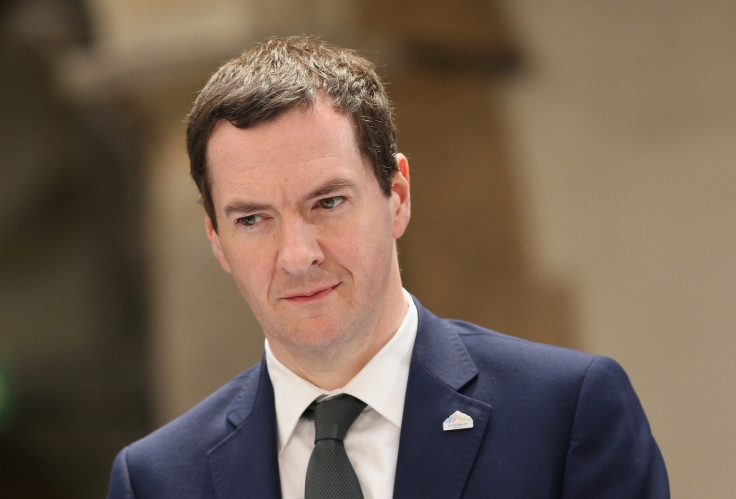

The UK chancellor, George Osborne, talked a good game on entering office in 2010 about kicking out the consultants in an age of austerity. And so the UK government did, for a time. But when fiascos such as the botched West Coast franchise renewal in 2012 occurred, it became clear what can happen inside government departments when they go short of business acumen for short-term budgetary reasons.

Caveat emptor applies when buying in consultancy as in anything else. Should you offer variable fees, that is, pay for performance? Will the consultants help carry out their advice? Will "knowledge transfer" take place, that is, will you as a client learn how to do useful stuff? And will the consultants leave the building promptly once the project has been completed?

Whatever the prospects for the rest of the economy, I doubt we should have too many fears about the future for management consultancy. A nice line in the MCA annual report states that: "While the Digital Revolution is under way, it has scarcely begun." Should a forecast like that prove accurate, consultants will remain busy for some time to come.

Stefan Stern is a business, management and politics writer. He writes for The Guardian and The Financial Times and is a visiting professor at Cass Business School.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.