UK Economy: Five Reasons to Fret about the Recovery

Britain's economy is on the mend, reckons Chancellor George Osborne, as GDP growth accelerates to 0.6% in the second quarter- a whole 0.3% higher than in the year's opening three months.

Yet the numbers underneath the GDP figure are still telling a troubling story about the UK.

The economy may be growing more than it was before, but our incomes are falling, the labour market is frail, and our colleagues across the globe are staring at a slowdown.

To focus on the headline GDP number and claim the economy is mending is a bit like saying: "I've got leprosy, cancer, the clap, tuberculosis, and malaria - but at least I haven't got a headache anymore."

Here are five reasons we shouldn't get the bunting out just yet to celebrate our victorious emergence from the slump.

Long-term Unemployment is Rising

The number of people out of work for more than a year in the UK economy hit 909,000 in the three months to June, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), a rise of 7,000 on the previous three months. On the same period a year before, this was a 27,000 increase.

This means that more money will be spent on getting the long-term unemployed back into work and keeping them above water with welfare. It also means potential output and tax receipts are both lost because of their labour market dormancy.

So is Youth Unemployment

There were 973,000 young people out of work in the UK during the second quarter, said the ONS, a 15,000 rise on the three months to March.

This problem is arguably more potent than long-term unemployment, given the effects early joblessness can have on an individual's health and life chances, coupled with the costs of preparing them for work and supporting them while they're out of it.

Underemployment is Rife

Those fortunate enough to be in work aren't necessarily having their needs fulfilled.

The number of people in employment, but who want or need to work more hours, has risen in total by a million since the financial crisis hit the UK in 2008, according to the ONS.

What's more, the labour market is shifting away from secure employment and towards the precariousness of zero-hours contracts, temporary work and self-employment.

Research by the Trades Union Congress found that temporary jobs account for around half of the rise in employment since 2010. It also found the number of involuntary temporary workers - those who want a permanent job - has shot up by 155% since 2005, to 655,000 people.

The Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development estimates there to be at least a million UK workers on zero-hours contracts, which offer no contractual guarantee of working hours each week.

Incomes are Still Falling in Real Terms

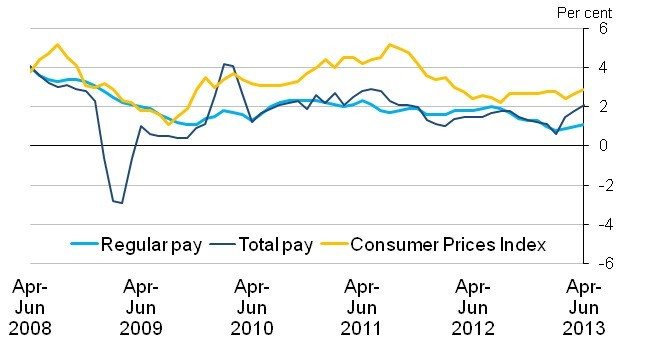

For four years now, regular pay his risen below consumer price inflation, meaning we're paying more out on our bills and getting less in from our jobs.

In the three months to the end of June, regular pay - which excludes bonuses - rose by just 1.1%. Inflation was 2.9% in June.

Here's a chart from the ONS showing how long the wage decline has been going on:

Research by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation calculates that the basic cost of living in the UK has risen 25% since the financial crisis, as wages plummeted.

We're also paying more of our earnings on rent too, as the shortage in supply of affordable homes holds up house prices and therefore underpins stinging rents. Here's a chart from Nationwide:

The IMF Keeps Cutting its Global Growth Forecast

Chancellor George Osborne wants to increase the value of UK exports to £1tn by the end of the decade, but that - and the domestic economic success to be derived from it - depends on the health of the country's trading partners.

Europe, our biggest export market, is still mired in crisis and recession. While the eurozone bloc pulled out of its 18-month recession at the end of June, this was largely due to a slightly better than expected performance from Germany and France.

Other big eurozone economies, such as Spain and Italy, are still wallowing in recession and there remains a significant amount of fiscal restructuring and painful austerity to be undertaken in periphery countries, such as Greece and Cyprus.

Looking further afield, China - one of the UK's target markets for exports - has had a number of leading analysts slash their growth forecasts for the Asian powerhouse.

Britain is targeting high growth Asian markets and the Brics in an effort to drum up trade, but the International Monetary Fund's most recent World Economic Outlook report slashed its global growth forecast for the fifth consecutive time, to 3.1% for 2013.

"After years of strong growth, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa are beginning to run into speed bumps," said Olivier Blanchard, the IMF's chief economist.

"While growth in emerging countries has slowed, inflation has not fallen with it

"This has an important implication: that growth in emerging markets will remain high, but maybe substantially lower than it was before the crisis."

Lower global growth means fewer trade opportunities for the UK.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.