Who are the Rohingya and why are they desperate to flee Myanmar?

The Rohingya are effectively stateless. Neither Bangladesh nor Myanmar recognises them as citizens. They live in apartheid-like conditions.

In the last week, nearly 125,000 Rohingya Muslims have left their homes in Myanmar and crossed into Bangladesh, fleeing violence and persecution.

Buddhist-majority Myanmar's treatment of its Rohingya population is the biggest challenge facing Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung Sang Suu Kyi. Malala Yousafzai, the youngest Nobel Peace Prize winner, has said "the world is waiting" for Suu Kyi to speak out about the "shameful" treatment of the Rohingya.

Who are the Rohingya and why are they desperate to flee Myanmar?

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority in predominantly-Buddhist Myanmar, also known as Burma. They are concentrated in western Rakhine state, which is adjacent to Bangladesh. Their numbers have been estimated at about 1.1 million.

The UN says the Rohingya are one of the most persecuted groups in the world. Neither Bangladesh nor Myanmar recognises them as citizens. In Myanmar, even the name Rohingya is taboo. Myanmar officials refer to the group as "Bengalis" and insist they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, even though most have lived in the country for generations.

The Rohingya are effectively stateless. They have limited access to education or adequate health care and cannot move around freely. They have been attacked by the military and chased from their homes and land by extremist Buddhist mobs in a country that regards them as illegal settlers.

Longstanding tension between the Rohingya Muslims and ethnic Rakhine Buddhists erupted in bloody rioting in 2012 that killed nearly 200 people and displaced 140,000 – most of them into crowded camps just outside Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine state, where they live under abysmal, apartheid-like conditions, with little or no opportunities for work.

Over the years, tens of thousands have attempted to flee across the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea to Thailand and Malaysia. The conditions at home – and lack of job opportunities – sparked one of the biggest exoduses of boat people since the Vietnam War. A crackdown on people smuggling networks in Thailand in 2015 saw many Rohingya abandoned at sea by traffickers.

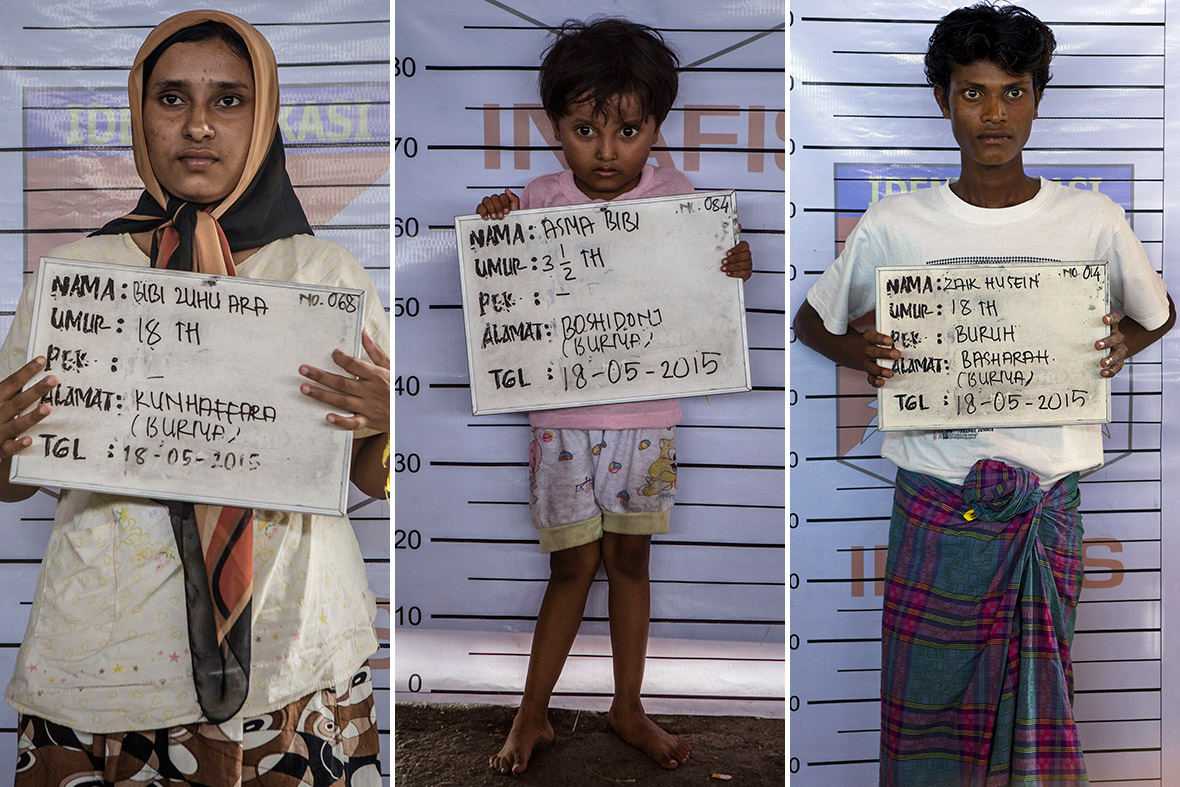

The plight of the Rohingya made front pages around the world in May 2015, when a boatload of Rohingya and Bangladeshi refugees was found adrift in the Andaman Sea off Thailand. The desperate and dehydrated passengers said they had been onboard the boat for three months after being abandoned by people smugglers who had enticed them with promises of jobs in Malaysia. They were eventually rescued at sea and transferred to migrant camps in Indonesia.

Many others were found imprisoned in jungle camps in Thailand and Malaysia, being held until their relatives back home could give money to the smugglers in return for their freedom.

About 210,000 Rohingya have sought refuge in Bangladesh since October 2016, when Rohingya insurgents staged attacks on security posts, killing nine officers.

The army responded with a savage counterinsurgency sweep that lasted months and, according to human rights groups, left entire villages burned to the ground. The United Nations accused security forces of gang-raping women and carrying out extrajudicial killings of children, even babies. The world body says some of the atrocities could amount to crimes against humanity. The Myanmar government and military denied the accusations.

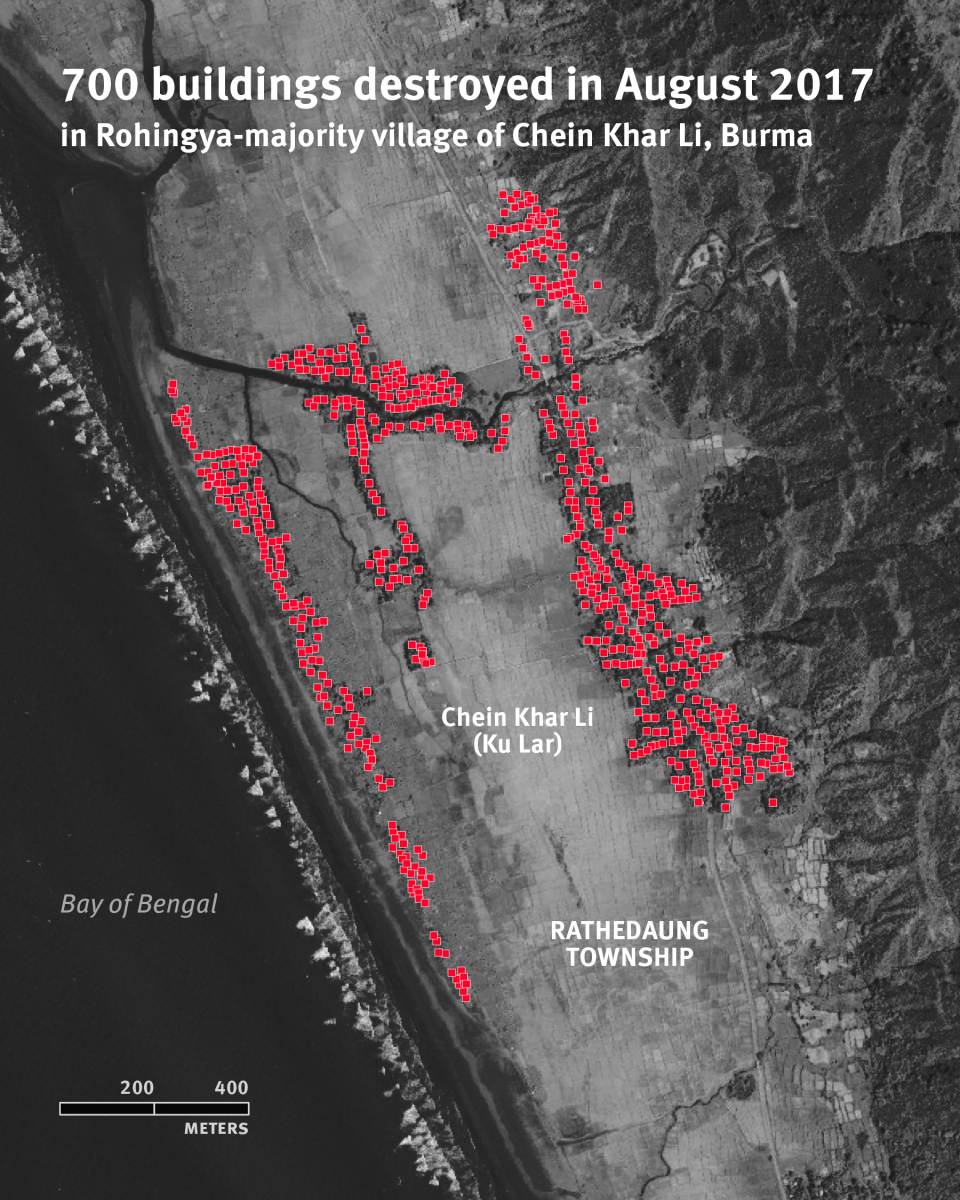

Before-and-after satellite images released by Human Rights Watch showed Rohingya villages in Myanmar's troubled Rakhine State that were allegedly burned down by soldiers. Swipe across these images to see the scale of the destruction.

Journalists and other outside observers have been unable to independently travel to the northwest of Myanmar's Rakhine state since the outbreak of violence last year. The government circulated a photo showing energy biscuits donated by the UN World Food Programme that it said were discovered in July at an insurgent camp. The photo was widely reposted on social media as alleged proof of complicity with the insurgents.

The UN and aid groups have had to suspend operations in Rohingya camps following government accusations of supporting insurgents. This means thousands of Rohingya Muslims in camps in Myanmar's Rakhine state are not receiving food supplies or healthcare.

Myanmar Security force found 2 rice bag which has pressed #WFP, #USAID name from #Terrorist Camp.#Condemn #terrorist. pic.twitter.com/SUDkBgY4qJ

— Aeindra (@DipperYour) August 29, 2017

The latest violence in Myanmar's northwestern Rakhine state began on 25 August, when a Rohingya insurgent group wielding sticks, knives and crude bombs carried out coordinated attacks on more than 25 Myanmar police posts and an army base. An Islamist insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, or ARSA, took responsibility for the attacks, saying they were in defence of Rohingya communities.

The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army was formed last year by Rohingya exiles living in Saudi Arabia, according to the International Crisis Group. It is led by Attullah Abu Amar Jununi, a Pakistani-born Rohingya who grew up in Mecca, and a committee of about 20 Rohingya emigres. ICG says there are indications Jununi and others received militant training in Pakistan and possibly Afghanistan. Analysts blame Myanmar's government for the conditions that led to the group's creation. The lack of a political solution to their plight, particularly after the anti-Muslim violence in 2012, helped sow the seeds for armed rebellion.

Human rights groups and advocates for the Rohingya say the army retaliated by burning down villages and shooting civilians. The government blames Rohingya insurgents for the violence, including the arson. Myanmar says its army is conducting clearance operations against "extremist terrorists" and that security forces have been told to protect civilians, but Rohingya arriving in Bangladesh say a campaign is under way to force them out.

Eyewitnesses told a human rights watchdog that Rohingya Muslims are being beheaded and burned alive as Myanmar's army continues to persecute women, men and children living in the Rakhine state. One man who fled into Bangladesh told Reuters: "Myanmar doesn't distinguish between the terrorists and civilians. They are hunting all the Rohingya."

Men in the Kutapalong makeshift camp on the Bangladesh side of the border told Reuters that many of the Muslim villages near the border were empty, and that troops and ethnic Rakhine Buddhists had set fire to homes. Satellite imagery analysed by New York-based Human Rights Watch showed widespread burnings in at least 10 areas in northern Rakhine since the coordinated attacks.

Nearly 90,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled violence and persecution in the last week. While most have crossed into Bangladesh by land, some have drowned after attempting the more dangerous boat crossing over the Naf River that separates the two countries. Bodies of refugees, many of them children, have washed up on Bangladesh shores.

The new arrivals – many sick or wounded with burns or bullet wounds – have strained the resources of aid agencies and communities already helping hundreds of thousands of refugees from previous spasms of violence in Myanmar. "One camp, Kutapalong, has reached full capacity," said Vivian Tan, the regional spokeswoman for the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR.

The independent Burma Human Rights Network said that the systematic persecution of minority Muslims is on the rise across Myanmar and not confined to the northwestern state of Rakhine. The report says many Muslims of all ethnicities have been refused national identification cards, while access to Islamic places of worship has been blocked in some places.

At least 21 villages around Myanmar have declared themselves "no-go zones" for Muslims, backed by the authorities, it said. The report says the persecution is backed by the government, elements among the country's Buddhist monks, and ultra-nationalist civilian groups.

There are also reports of Muslims being blockaded inside their villages by their Buddhist neighbours. Residents, aid workers and monitors told Reuters that Muslims had been blocked from going to work or fetching food and water for weeks.

Countries with large Muslim populations, including Bangladesh, Indonesia and Pakistan, have called on Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi to halt violence against Rohingya Muslims.

Now the rest of the world needs to wake up to what is going on in Myanmar. As Daniel Hannan writes in this IBTimes UK piece, part of the problem is perception: the victims are largely Muslim, and the persecutors are largely Buddhist – a religion we associate with martyred Tibetans and Californian hippies. Aung San Suu Kyi is established in our world-view as a victim of almost saintly qualities. We don't like the idea that she might be turning a blind eye to atrocities for the sake of appeasing the generals, let alone that she might herself be flirting with Buddhist nationalism.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.