Why Turkey's Ground Won't Stop Shaking: Inside the Simav Fault Swarm

After two 6.1-magnitude quakes in just two months, scientists say the Simav Fault beneath Balikesir is restless and residents are running out of calm.

Western Turkey has barely had time to recover from one quake before the next one hits. On Monday night, panic swept through the province of Balikesir after a 6.1-magnitude earthquake struck the town of Sindirgi, toppling weakened buildings and sending terrified residents into the streets as torrential rain poured down.

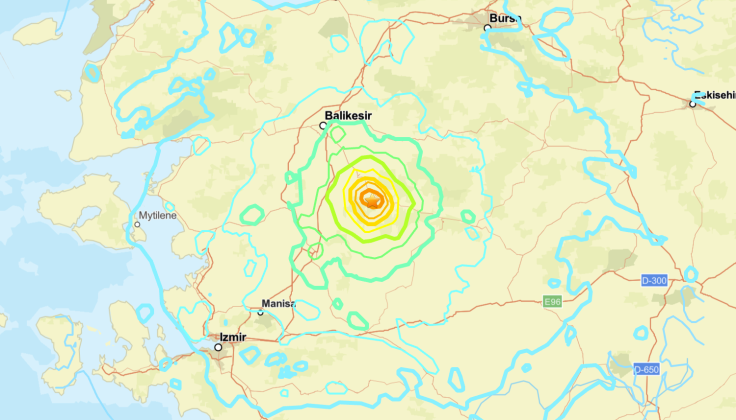

The tremor, which hit shortly before 11 p.m. local time, was strong enough to be felt as far as Istanbul and the nearby provinces of Bursa, Manisa and Izmir.

According to the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD), at least 22 people were injured, most from panic-related falls as thousands fled their homes in fear.

Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya confirmed that several derelict buildings and a two-storey shop collapsed, while others were left cracked and unsafe.

Many residents refused to return indoors, spending the night outside or seeking refuge in mosques, schools and sports halls opened by authorities.

Heavy rain only added to the fear and discomfort as rescue teams worked through the night.

It was the second 6.1-magnitude quake to hit Balikesir in just two months. The previous one, in August, killed one person and injured dozens. The back-to-back tremors have reignited concern about the region's fragile state and its growing exposure to further earthquakes.

Why the Ground Keeps Shaking

Experts believe the repeated quakes are linked to an underground fault known as the Simav Fault, which runs beneath southern Balikesir. It forms part of a wider network of cracks called the Aegean Graben System, one of the most earthquake-prone regions in Turkey.

In simple terms, Turkey rests on a massive slab of the Earth's crust known as the Anatolian Plate, which is being squeezed and pushed westward by neighbouring land masses.

Over time, pressure builds up along the Simav Fault like a tightly wound spring until it suddenly slips, releasing energy as an earthquake.

Sometimes, one quake can disturb nearby sections of the same fault, triggering another soon after. Scientists call this sequence a 'fault swarm', a cluster of moderate earthquakes that strike over a short period rather than one catastrophic event.

A study published in GeoHazards found that after August's quake, more than 10,000 smaller aftershocks occurred in the same area, suggesting that the Simav Fault remains highly unsettled.

This swarm-like behaviour, while unnerving, may have prevented an even greater disaster. Because the stress is released gradually through smaller quakes instead of one massive rupture, the energy spreads out over time, strong enough to rattle buildings but not to level them completely.

The Hidden Weakness Above Ground

While the ground beneath Balikesir continues to move, what stands above it remains dangerously fragile. Many buildings, especially in smaller towns such as Sindirgi, were constructed before Turkey introduced stricter earthquake safety codes in the early 2000s.

Several structures already damaged in August could not withstand another jolt. One older concrete building collapsed entirely, and a mosque minaret was left cracked and leaning. The area's soft soil also amplifies tremors, making even moderate quakes more destructive.

Preparing for the Next One

The Simav Fault has been active for more than a century, with major earthquakes recorded in 1900, 1944, 1969 and 1970. Experts warn that the latest tremors are part of a continuing pattern that shows no sign of stopping.

Authorities are now inspecting damaged buildings, setting up temporary shelters and urging residents to remain cautious. Scientists stress that stronger building standards and public awareness are crucial to saving lives when the next quake strikes.

In western Turkey, it is not a question of if, but when.

For the people of Balikesir, the ground may have stopped shaking for now, but the fear and the uncertainty remain.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.