Is Duterte's war on drugs really a war on the poor? [Graphic images]

Drug use is often a symptom of social problems, not the cause. Where there is demand, there will be supply.

Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte's promises to cleanse the streets of drug pushers and rescue the next generation of Filipinos from the scourge of narcotics have won him the support and trust of his people. In his inaugural State of the Nation address, he promised: "We will not stop until the last drug lord ... and the last pusher have surrendered or are put either behind bars or below the ground, if they so wish."

More about Philippines' bloody war on drugs from IBTimes UK: Four charts reveal President Duterte's unprecedented purge

However, most of the over 1,500 people killed by the police and hundreds more summarily executed by unknown assailants were not drug lords, but either small time dealers selling shabu (as methamphetamine is known locally) to raise themselves out of poverty, or light drug users who would occasionally scrape together enough money to buy a sachet of shabu to escape the misery of Manila's shanty towns.

Some of those killed may not have been involved in drugs at all – they may simply have made a few powerful enemies who wanted them out of the way. Whether they were guilty or not may never be known. In the case of police shootings, witness reports often differ widely from the official versions of events. Local authorities known as barangay captains supply the police with lists of "drug personalities", meaning suspected users or dealers, most of them small-time. Police say they then "validate" these names in consultation with national anti-narcotics and intelligence officials. They also add names of their own.

These watch lists are meant to be confidential, but so-called "knock and plead" operations, in which police visit drug suspects at their homes and urge them to mend their ways, means inclusion on a list is often public knowledge. Drug dealers and users are also urged to "surrender" to the police at barangay meetings that are, again, public. The process resembles a mass arrest. Roughly 700,000 supposed addicts have come forward to register with the authorities.

Human rights monitors and some officials warn that the process is open to abuse. Lists have included the names of people "who are not even drug users, never mind pushers," Karen Gomez-Dumpit, a commissioner at the Philippines' Commission on Human Rights, told Reuters. "It's an environment conducive to someone with a grudge and a gun to hunt you down," she said.

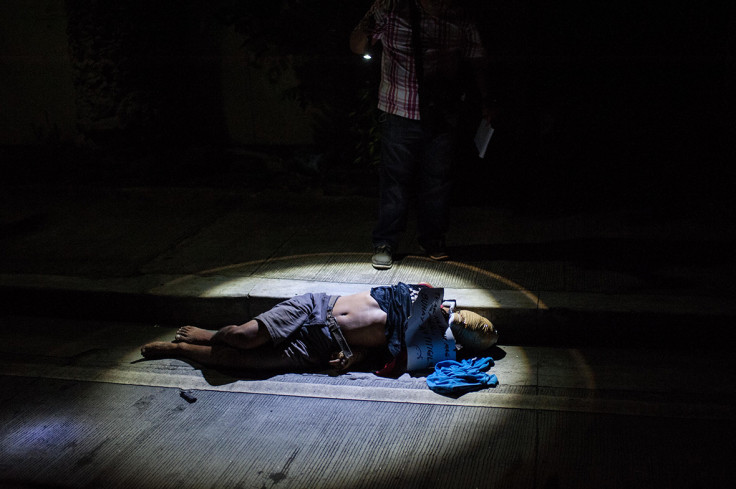

In the case of extrajudicial killings, the only evidence is often a sign around the neck claiming the deceased was a drug dealer. In one high-profile case, the bullet-riddled body of Mark Culata was found in Cavite, a province south of Manila, on 9 September. It bore a placard identifying him as a drug dealer. Culata's mother Eva told local media that her 27-year-old son had nothing to do with drugs and had been heading overseas to start a job. Police told Reuters in a statement that investigators were considering the "illegal drug trade and love triangle" as possible motives.

Public criticism of Duterte is rare. He has a 76% satisfaction ratingand has quashed opposition to his war on drugs and blasted critics in curse-laden language. In interviews with Reuters, more than a dozen clergymen in Asia's biggest Catholic nation said they were uncertain how to take a stand against the thousands of killings in a war that has such overwhelming popular support. Challenging the president's campaign could be fraught with danger, some said.

Father Luciano Felloni, a priest in a northern district of the capital, said at least 30 people, including a child and a pregnant woman, have been killed in his 'barangay', or neighbourhood. "There is a lot of fear because the way people have been killed is vigilante-style so anyone could become a target ... There is no way of protecting yourself," he said. Another priest, who asked for anonymity because of possible reprisals, said it was risky to question the killings openly. Dozens of drug addicts and pushers are being killed every day, but anyone who criticises Duterte's campaign could suffer a similar fate, he said.

Duterte, who is not a regular church-goer himself and says he was sexually abused by a priest as a boy, has publicly questioned the Church's relevance and he dubbed May's presidential election a referendum between him and the Church.

In a rare criticism of Duterte from a political leader, 88-year-old former president Fidel Ramos said Duterte's government has been a "huge disappointment and letdown" and is "losing badly" by prioritising the war on drugs at the expense of issues like poverty, living costs, foreign investment and jobs.

The Commission on Human Rights said the war on drugs "has targeted and negatively affected" the poor. The Asian Development Bank estimates that a quarter of Filipinos live in extreme poverty. Estimates put the number of street children in the country at 250,000. These are the people who suffer most from Duterte's various crackdowns. Police conduct door-to-door operations in Manila's slums. Armed police round up children, drunks and shirtless men in an effort to clean up the streets of the city.

Critics say Duterte's heavy-handed approach will not only fail, but make matters worse. Writing in Business World Online, Dr John Collins, Executive Director of LSE's International Drug Policy Project, says: "One cannot solve a public health issue through repression and criminalisation. It forces consumers into dangerous situations and increases risky practices. Expect higher levels of HIV, Hepatitis C, and other costly and avoidable illness in the aftermath of this war. When forced to hide their usage practices people do irrational things, such as sharing syringes and consuming in dangerous environments."

In the Philippines, as elsewhere, drug use is often a symptom of social problems, not the cause. Where there is demand, there will be supply. The US and many European nations are realising they can never win a war on drugs, and instead are moving towards educating drug users about harm reduction and treatment.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.