Kurdish genocide in Iraq: Survivors tell their stories

Wherever he goes, Kamaran Haider carries with him a faded photograph of dead bodies cluttered outside his house in Halabja, in the Iraqi Kurdistan. The bodies, captured in the last throes of life, belonged to his mother, father, brothers and sisters. His loved ones were among the 5,000 people who died in April 1988 in one of Saddam Hussein's most atrocious chemical attacks against the Kurdish population.

Kamaran survived by hiding in a makeshift bomb shelter dug by his father in his garden. He was only 11 years old at the time. He still has a lingering cough to remind him of the poisonous attack as a sort of scar, the ironic legacy of mustard gas and nerve agent. In a bizarre twist of fate, one of the consequences of chemical agents is a deficiency in Kamaran's short-term memory. Halabja, conversely, is glaringly imprinted in his mind.

Iraq launched the attack on Halabja during the last gasps of the country's eight-year long war with Iran in response to the brief capture of the city by Iraqi peshmerga - Kurdish fighters - assisted by Iranian revolutionary guards. But the mass gassing was not an isolated episode. Along with Saddam Hussein's genocide campaign called Anfal, and the persecution of Faylee Kurds in the 1970s and 1980s, Halabja stands out as a systematic and deliberate intent on the part of the Baathist regime to destroy, through mass murder, Iraq's Kurdish minority.

The Iraqi Kurdistan Regional Government has launched an e-petition urging the British government to recognise the mass murder of Kurdish people during the regime of Saddam Hussein and the overlord Ali Hassan al-Majid, aka Chemical Ali, as genocide. Although Iraq, Sweden and Norway have already endorsed this definition, the Government has stated that "it is not for governments to decide whether a genocide has been committed" as it is up to the international judicial body to determine whether or not a crime is genocide.

"We felt a strange smell, like garlic or apple"

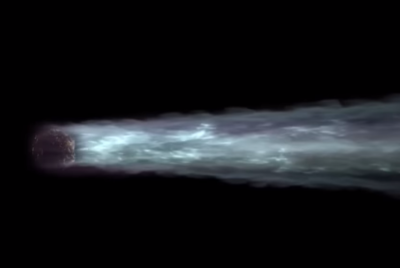

Kamaran's family had heard that poisonous attacks had occurred in nearby villages. But on 16 March 1998, the air in the village was vibrant with joy for the recent liberation by peshmerga. Minutes before the attack, Kamaran was playing with his little brother in the garden. Then, Iraqi planes made their appearance in the sky.

"People started screaming and we ran to the shelter, along with neighbours and friends," Kamaran recounted. "We wanted to leave the city but Iraqi military used intelligence tactics. At the beginning, they launched napalm bombs to keep people inside their houses and shelter.

"After one or two hours we felt tears dropping from our eyes and a strange smell, like banana, garlic or apple," he said. "We knew it was a chemical bombardment. It is horrible because it's not like other bombs: the chemical is mixed with the air. You can't run. You can't do anything."

Lacking even the most rudimentary gas masks, Kamaran's mother went upstairs to bring wet papers and towels to lay on her family's faces and hands to prevent them from burning. She came back. One chemical bomb was dropped in the neighbourhood's house. That is when the tragedy happened.

"My older brother named Rewar, three years older than me, ran out of the shelter and said 'I'm going to see what's going on'," Kamaran said. "My mum and my dad shouted 'Don't go there' but you know how young people are...He did not come back. My mum decided to go out to see what happened to him. A few minutes later we heard her screaming 'Rewaar is dead'. She came downstairs, and dropped off, dead."

"I just knew that people died, that's it"

Kamaran resisted the impulse to get out, and stayed inside the shelter. His sister and older brother, instead, went out. He started feeling sick, worn-out, exhausted. His skin was aching and his body was burning. He did not know who was still alive inside the shelter.

"After a few hours it was very quiet. I just laid there with no food and no drink. I tried to drink water from the towels my mum brought to us," Kamaran said. "A friend of mine was next to me. He kicked the can and said 'don't drink that it's dirty'. The water was poisoned."

Minutes, hours and days passed, and Kamaran alternated an unconscious to half-sleep state.

"I lost my feeling, all my feeling," he recounted. "I knew that my mum died. I knew that my brother died. I know all that people died but I lost my feeling because the chemical affected me physically and mentally.

"At that time, I didn't cry," Kamaran said. "I didn't feel anything. No happiness, no stress. Well, I knew that people around me died, that's it."

"Then I went out, like a baby crawling from the stairs. I saw all my family, dead. My brother died in one side. My sister was holding my brother, their heads tended together. I could see my father dead in front of the bathroom, far from the shelter."

Kamaran launches into a chilling, detailed description of the architecture of Iraqi Kurdish houses that contrast somehow with the scene he faced. He got back to the shelter, but his eye turned completely blind. Only a few days after Iranians guards arrived to the shelter and rescued him. "I tried to speak but I couldn't. I didn't see. So I held up my hands so they knew I was still alive."

"I never lived my childhood"

Thana Al Bassam is a Faylee Kurd, one of the most persecuted Kurdish communities under Saddam Hussein's regime. "They consider us as Kurd on one side and Shia on the other side," she told IBTimes UK. "I come from a very rich family that hold economic power in Baghdad."

The Faylees were targeted in the 1970s and 1980s by the Baathist regime that saw them as a "Persian threat". They were removed from their homes and sent to the Iranian border. In April 1988, Thana lost 22 male relatives overnight, who were arrested and separated from their families.

"I still remember it was the 6 April," she said. "It's stuck in my mind because the next day, when I went to school, the teacher wrote that date on the board."

Thana and her parents forced to leave the house in a hurry, and found themselves in the street. They sought refuge in Iran. "That's the start of a new dramatic story," she recounted. "I never lived my childhood, I never had a teenage normal life. I was scared all the time. We were hiding in fear."

Thana moved to Britain in 2004. She strongly supports the Kurdistan regional government's call to the British government to recognise the mass murder of Kurdish people in Iraq as genocide. "No-one can imagine how difficult it was to live under Saddam Hussein's regime," she said. "It happened ten years ago but sometimes I feel 'Oh my God, is he really gone?' I keep asking myself this question every time."

Written by Gianluca Mezzofiore