Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 Would Have Been Found If Communications Box Had $10 Upgrade

The missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 might have been found by now if a small communications box on the plane had been configured to send out more frequent reports, according to British satellite communications firm Inmarsat.

Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 took off from Kuala Lumpur International Airport for Beijing with 239 people onboard at 00:41 local time on 8 March but lost contact with air traffic control 50 minutes later.

It has now emerged that the airplane's Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (Acars) system was deliberately turned off, yet the Boeing 777 plane still continued to send out "pings" to Inmarsat's satellite for seven hours after it lost contact.

The pings are small bursts of data which are sent out by the satellite network to the plane every hour to check if it is still on the network, and according to Inmarsat, Flight MH370 sent out seven hourly pings in response to the network's request.

"When the plane was still missing on Sunday (the day after it disappeared), our engineers looked at the network data and realised that the plane had been sending signals," Inmarsat Senior Vice President Chris McLaughlin told IBTimes UK.

"We couldn't say what direction it had gone in, but the plane wasn't standing still because the signals were getting longer, i.e. further in distance from our satellite."

Data transmissions not mandated

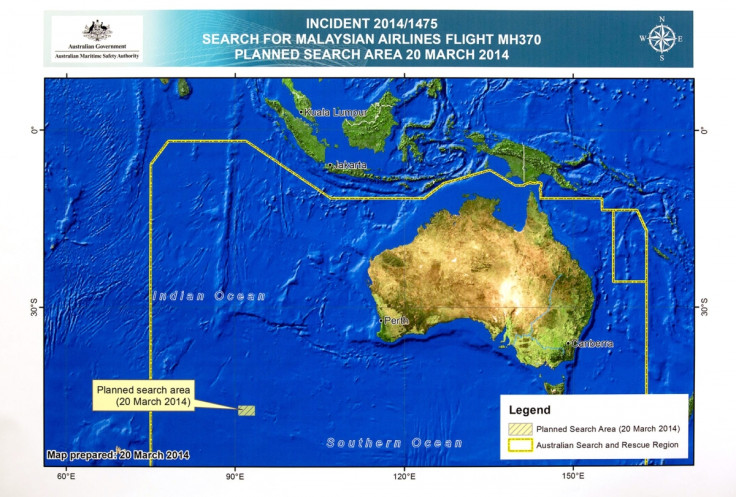

The hunt for the missing plane has been going on for the last 12 days and 26 countries have joined in to search. The latest lead pointed to two large objects floating in the southern Indian ocean, but nine hours of searching found only a freighter and two schools of dolphins.

Critics of the aerospace industry are now calling out its "outdated" accident investigation process and asking for data from the black box to be streamed in-flight to the cloud, which could be expensive, but McLaughlin says that the plane could have been found by now if the communications box buried in the plane's avionics had been configured to send out more frequent reports.

"What we have at the moment would have been fine if the airlines had been mandated to provide data on all their flights. The only area where data is mandated is on the transatlantic route, which is so busy that everyone needs to know where all the other planes are," he said.

"We may never know what happened to the plane because the cockpit is not mandated to be monitored in other areas, and we urge regulators to look into this."

The Inmarsat Classic Aero is installed in 90% of the world's commercial jets, and it is this little box which sent out the pings of information.

The box has been in use "for decades" and sends information to the Inmarsat-3 and Inmarsat-4 satellites stationed in the geosynchronous belt 22,300 miles above Earth.

Only costs $10

"You really do need to know the height, distance, direction and a record of what has been going on the flight deck in a regular burst every 15 to 30 minutes," said McLaughlin. "If the box had been configured to send out these bursts, we would have located the plane by now."

Configuring the box is up to each individual airline operator but receiving data from a five to seven hour flight would only cost $10 (£6) per flight.

Air France Flight 447 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean in 2009 but within five days, major wreckage had been removed by the Brazilian Navy, because Air France had configured their Classic Aero box to send back information every four minutes.

The black box, however, took another two years and €32m to retrieve from the ocean floor.

An upgrade to Classic Aero is currently going through testing, called SwiftBroadband. The new product will give 512Kbps of broadband to flights, which would be enough to send text messages, make phone calls, and crucially, to stream information into the cloud.

"When it takes two years to find a black box, you're looking for a needle in a haystack, and technology has moved on now. You need both the ability to burst/stream information off the plane in real-time, and you need a black box in case of a [disaster] so we can find out what happened," McLaughlin stressed.

"Streaming information about the flight into the cloud would work with 512Kbps as you're talking about small bits of text-based data, no graphics, no video, just kilobits, not megabits."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.