What Price Royal Mail Shares? The IPO's Critics are too Harsh on Vince Cable

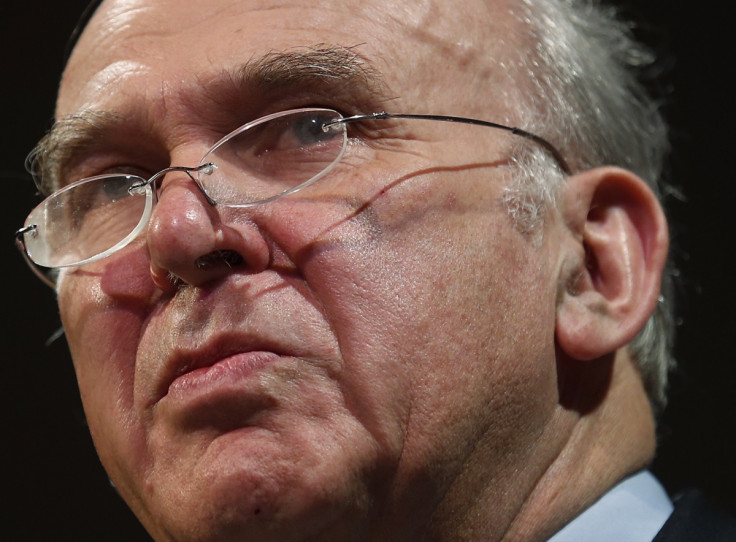

It seems like every week that someone lobs another brick at the government, Business Secretary Vince Cable in particular, over the privatisation of Royal Mail.

That Royal Mail's share price is, at the time of writing, around 80% above its offer price just five months on from the flotation doesn't help the government's case that it properly valued the firm.

But it's not as simple as many commentators suggest, particularly those who appear to think you can launch IPOs at whatever price you want and expect markets to come begging.

The government and its advisers could only work from what they were told by large institutional investors, the sort being targeted in the Royal Mail sale.

And that advice was they would walk away at an offer price of over 330p, a threat that could have left the flotation a total disaster. Would it be worth the risk of assuming they were bluffing? No, it would not.

As the price soared in the weeks and months after the initial public offering, it was supported by the limited supply of shares because long-term investors were holding on to their stock – just as the government had hoped. Couple this with hot demand and of course the share price will soar.

According to a research note from Barclays, the average daily volume of Royal Mail trading is 3.5 million shares. There are a billion Royal Mail shares in issuance. That means just 0.35% of Royal Mail shares are being traded on a daily basis.

Most people are hanging on to their Royal Mail shares and that should be seen as a success.

A criticism repeatedly hurled at the government is that many other banks valued Royal Mail much more highly than the two official advisers, Goldman Sachs and UBS. But these two were the only banks with full access to Royal Mail.

While other analysts can draw opinions from the available data, and have come up with a higher valuation than Goldman and UBS did, they were not privy to all of the information and so could not make a fully informed conclusion on how much Royal Mail was worth.

Who do you better trust to come up with a decent valuation that is realistic in the long-term: those with half of the information or those with all of it?

There were two other major pressures on the government to ensure a clean, successful IPO of Royal Mail that saw all of the shares sold off to hungry investors with appetites whetted by an attractive offer price.

Firstly, a botched IPO would make it harder for Royal Mail to access capital markets in the future. It may need to raise cash to invest in expansion and job creation by issuing more of its equity.

Royal Mail has not been tainted by a disappointing IPO, leaving the door to capital markets wide open.

Secondly, the Royal Mail IPO cannot be seen in a vacuum. There are two other major government sell-offs in the pipeline: Lloyds Banking Group and Royal Bank of Scotland.

The last thing the government – and taxpayers – need is one cocked-up IPO to create a bad smell around the sensitive noses of investors eyeing the eventual Lloyds and RBS sell-offs.

There is still a long way to go before we can fairly judge the offer price. Royal Mail was only privatised in October 2013 and there has so far been one financial report released by the firm.

The share price is still settling. It may fall dramatically, or rise even more, over the coming year as further financial reports are released and investors get a clearer idea of where Royal Mail is heading and how it is coping with a sharp decline in letters volumes.

Ignore those who say the Royal Mail IPO cost UK taxpayers billions of pounds. It cost us nothing. We might have made more money, but we are not out of pocket because of it. We didn't buy it and then sell it on at a lower cost. It is an asset we built up over hundreds of years.

Perhaps we could have squeezed a little bit more out of the Royal Mail sale – but at what cost?

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.