Sweden: Refugees dreaming of warm welcome in Scandinavian Utopia get the cold shoulder

Photographer David Ramos travelled around Sweden to document the daily lives of people stuck in no-man's land during the cold Scandinavian winter.

Sweden took in 163,000 asylum seekers last year, the most per capita in Europe, and double the previous record set during the Balkan wars. Refugees have long been drawn to the country's famed generosity and tolerance. Many fleeing increasing conflict and deprivation in the Middle East, Africa and Asia dream of a Scandinavian Utopia where they will be welcomed with open arms. The reality is often quite different.

The arrivals have put a huge strain on housing and other welfare services in the Nordic country. Summer holiday resorts, old schools and private buildings are being converted into temporary shelters for migrants and refugees as they wait for a decision on their asylum applications.

Photographer David Ramos travelled around Sweden to document the daily lives of people stuck in no-man's land during the cold Scandinavian winter.

Swedes may be politically liberal, but they are often culturally conservative: conformist, reserved and with strict social rules. Ylva Johansson, Swedish minister for employment and integration issues, says the problem is exacerbated by the fact that thousands of refugees, many young men, are not integrated into the workforce, instead languishing in asylum centres in villages and towns.

"Most Swedes are not racist," Johansson said. "But when there is this special asylum housing when they cannot work, and cannot be part of society this is really a tension. This is a dangerous situation; we have a lot of people in no-man's land ... living outside society."

In a National Review article titled, Torching Utopia, Tino Sanandaji – an Iranian Kurd who grew up in Sweden – writes: "The political and media elites may love or at least pretend to love the new multiculturalist society, but polls show that the Swedish public was never particularly enthusiastic about it. A recent study found that most native Swedes never socialise with immigrants or do so only rarely.

"From the point of view of immigrants, therefore, the Swedish state is warm and generous, but Swedish society is cold and distant."

Sweden has been proud of its open-door policy for decades – from taking in Vietnam draft dodgers in the 1960s to Balkans war refugees in the 1990s. However, in a country where speaking out against immigration is still taboo for many, Scandinavians privately voice concerns about crowded emergency rooms and larger school classes.

Newspapers are increasingly full of stories about money being spent on refugees and reports of crime involving asylum seekers, although crime figures do not bear out these concerns. For example, despite reports of refugees being linked to sexual assaults, reported rapes fell 12% in 2015, and thefts were down two percent.

Support for Sweden's centre-left Prime Minister Stefan Löfven has fallen to record lows in polls due to popular sentiment that his government is largely helpless to stop the influx of migrants and refugees seen as threatening Sweden's generous welfare state and vaunted social stability.

Anti-immigrant, populist parties have gained support over the past year, and the far-right is vying for top spot in polls. There are signs that voters may be broadly supportive of immigrants but not in their own backyard. From welfare cuts to new ID checks, it is a trend that shows the limits of even some of Europe's most liberal societies and may represent a sea change for politics in Scandinavia.

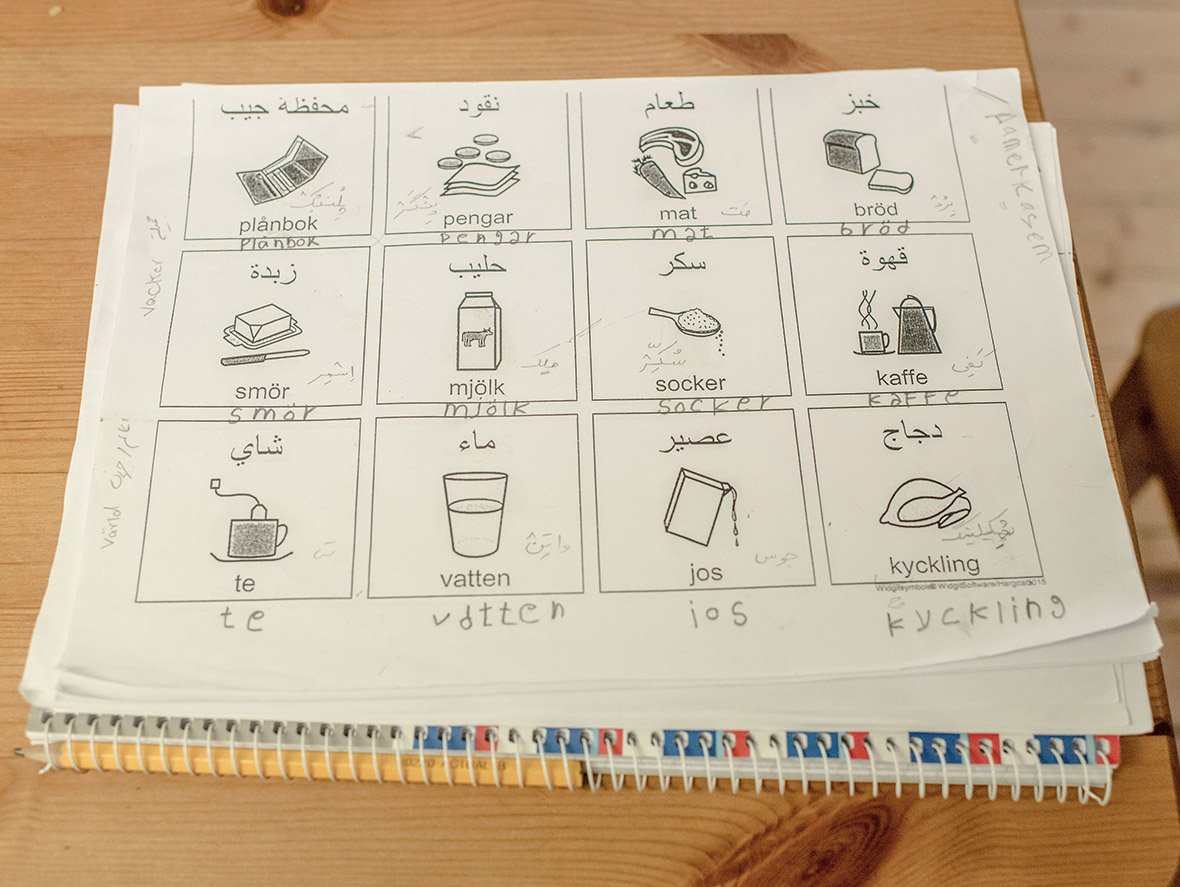

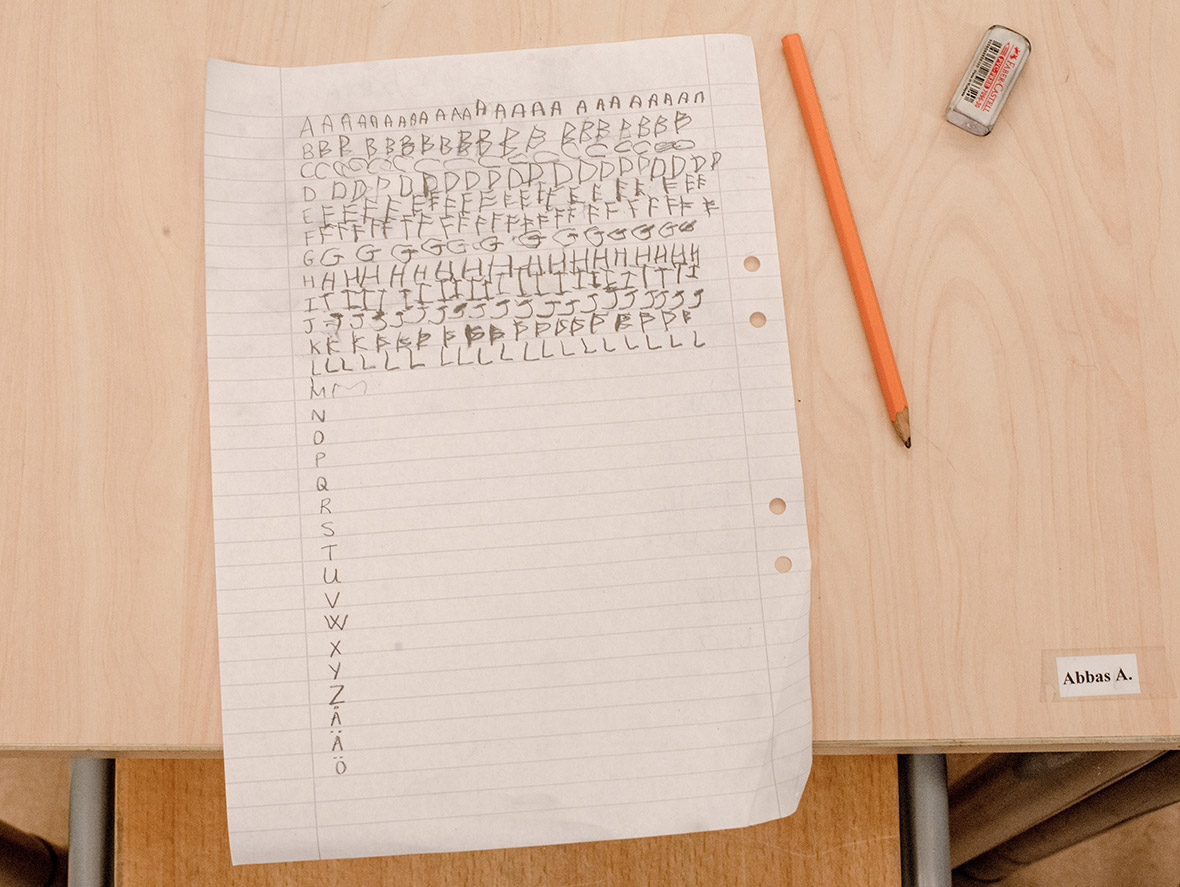

A survey in February 2016 showed immigration was the main concern for 40% of Swedes, easily trumping worries over failing schools, joblessness and welfare. The change was the biggest opinion swing in the poll's history. Sweden had to find an extra 70,000 school places due to the influx of asylum seekers, on top of 100,000 pupils that normally enrol in the school system for the first time in any given year.

The UN refugee agency says more than one million people crossed the Mediterranean into Europe in 2015 from the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere. The European Union is considering re-introducing border controls for up to two years between some of the 26 nations in the Schengen passport-free area to deal with the migrant crisis. Each country in the zone is allowed to unilaterally put up border controls for a maximum of six months. Now, policymakers are poised to invoke an emergency provision that allows for an extension of such controls for up to two years.

EU statistics show people make 1.3 billion crossings over the union's internal borders each year, while 57 million trucks transport goods worth hundreds of billions over those same borders annually. The free passage has also allowed some 1.7 million people to live in one country and commute to work in another. Cities such as Malmö in southern Sweden and the Danish capital Copenhagen have in effect fused, reflecting how the EU has turned from a community of nations separated by borders to one of regions. But in the wake of the refugee crisis, the whole idea of open EU borders has been called into question.

Sweden reversed its open-door policy on immigration late last year and introduced identification checks at its border with Denmark in an attempt to stem the flow. The country's migration agency expects up to 140,000 asylum seekers in 2016 but the government has said it will not allow numbers to get anywhere near that, vowing to introduce further measures to curb the influx if needed. Interior minister Anders Ygeman announced Sweden was preparing to deport up to 80,000 from last year's record number of asylum seekers, saying that if they did not leave voluntarily, they would be forcibly deported.

Nearly one in five people living in Sweden is of immigrant descent. Some 38% of the 386,000 registered as unemployed in the country are non-European migrants. The IMF estimates that Sweden will spend one percent of its GDP on asylum seekers in 2016, by far the highest of 19 European nations surveyed.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.